| |

April

2015

- Volume 9, Issue 2

Transcultural Adaptation of Best Practice Guidelines for Ostomy

Care: Pointers & Pitfalls

|

( (

|

Samar Ali

Abdul Qader

Mary Lou King

Correspondence:

Samar Ali Abdul

Qader

University of Calgary

Qatar

Email: samar16164@gmail.com

|

|

|

Abstract

Objective: No standardized guidelines for ostomy

care exist in the Middle East to support best practice.

This contrasts with North America where ostomy guidelines

are widely used in health service organizations. It

is unknown whether guidelines developed in one country

are relevant to other parts of the world. This project

sought to assess the relevance of North American ostomy

guidelines to a different health system and cultural

context in the Middle East. The overall aim was to reach

consensus to adopt, adapt or reject.

Methods: A graduate student, enrolled in a Masters

of Nursing (MN) program in the Gulf Cooperation Council

(GCC) state of Qatar, critiqued two North American guidelines

using standardized tools. The process engaged local

stakeholders and opinion leaders in the colorectal cancer

field, as well as international ostomy care and practice

guideline experts.

Results: Results of this critique, combined with

input from internal and external stakeholders, resulted

in a hybrid guideline that has been used in a Muslim

society with different demographic, health system and

cultural contexts.

Conclusions: Appraising the quality, content

and relevance of international ostomy guidelines to

different jurisdictions provided the opportunity for

local practitioners to define and shape best practice.

The adapted guideline is expected to promote consistent

standards of care and optimal health outcomes for persons

with ostomy in a region where cultural and religious

values are intricately linked to health beliefs and

practices.

Key words: Practice Guidelines; Adaptation; North

America; Middle East; Ostomy Care.

|

1. Introduction

International data indicate that colorectal cancer is the

third most common malignancy in the world, with 1.4 million

new cases diagnosed in 2012 [1]. In the Middle East, the incidence

of colorectal cancer is < 10 per 100,000 population; this

is substantially lower than North America, Australia and New

Zealand [2]. However, higher rates have recently been reported

in Israel and Qatar, where age standardized rates range from

30-40 per 100,000 population [1,2]. This is consistent with

findings of a study conducted in Qatar at the turn of the

century identifying that colorectal cancer rates in this small

Arabian Gulf country were higher than other Gulf Cooperation

Council (GCC) states, with the most common sites being the

sigmoid and descending colon [3]. Despite advancements in

oncology surgery in the past decade, ostomy formation remains

one of the major treatments for colorectal cancer [4]. As

such, stoma formation surgeries are on the rise around the

world concurrent with the increase in colorectal cancer.

An ostomy is an opening (stoma) from inside the small or large

bowel to the outside [5]. Ostomy can be permanent, when an

organ (the small intestine, colon, rectum, or bladder) must

be removed. It can be temporary, when the organ needs time

to recover. The most common ostomies are a colostomy, ileostomy

and a urostomy.

Patients with ostomy have physical, nutritional, spiritual,

health education and psychological support needs. It is important

for nurses, physicians and other health care providers to

understand the comprehensive needs of patients who have undergone

ostomy so they can provide responsive care. The goal of health

care providers is to assist patients with ostomies to achieve

optimal independence, self-care abilities, nutritional health

and bio-psycho-social-spiritual well-being. There is a trend

to standardize care and management approaches around the world

using clinical guidelines. The goal is to promote optimal

outcomes and reduce practice variation [6].

Clinical guidelines are systematically developed recommendations

to support provider and patient decisions about health practices

to achieve high quality care [6]. A facility and literature

review undertaken by a graduate nursing student in the GCC

state of Qatar revealed that no practice guidelines relevant

to ostomy care were in use in the Middle East. Furthermore,

no studies could be found that evaluated ostomy care of patients

with stomas in this part of the world.

Guideline adaptation is the systematic approach used to customize

an existing guideline to suit the local context; it is an

alternative to guideline development [7]. Decisions affecting

the adaption, adoption or rejection of guidelines are influenced

by several variables. These include the quality of the guideline,

the scientific evidence supporting the guideline, clinical

expertise, patient preferences, policies, culture and budget

[8]. Authors of the Abu Dhabi Declaration cite four reasons

that practice guidelines developed in one part of the world

cannot simply be adopted in other regions. They include: (1)

differences in culture, genetics, and environmental factors;

(2) variations in patients' presenting features and stage

of disease; (3) differences in health service access such

as technology or drugs; (4) evidence supporting the guidelines

may be generated from populations or contexts with limited

relevance to other jurisdictions [9]. A notable advantage

of adapting existing guidelines is to reduce duplication of

effort, while allowing health providers to integrate local

perspectives into the guideline content [10].

2. Methods

2.1 Purpose

Critiquing North American ostomy guidelines and assessing

their relevance to a different geographic and cultural context

was the focus of this student-led graduate project. The process

engaged local stakeholders and opinion leaders in the colorectal

cancer field, as well as international ostomy care and practice

guideline experts. The aim was to appraise the potential use

of guidelines developed in North America in the local context

and to reach consensus to adopt, adapt or reject. Engaging

Middle East health professionals in guideline appraisal enabled

clinical leaders to assert their critical thinking skills

and give input regarding the "fit" with the local

health system and the cultural-spiritual beliefs and values

of the population.

The following questions served as the focus of inquiry:

1. What practice guidelines currently exist in ostomy care

and management to support best practice of nurses and other

health care professionals?

2. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing ostomy

care guidelines?

3. What is the relevance of the ostomy care guidelines to

the Qatar health care system and population?

2.2 Philosophical Underpinnings

This work was philosophically grounded in the principles of

evidence-based practice (EBP) which involves the explicit

use of the current best evidence to make decisions about patient

care [11]. It involves augmenting health care providers' clinical

expertise with quality research data. Evidence-based nursing

(EBN), a subset of EBP, is the application of relevant, valid

evidence to inform clinical decisions, with consideration

of clinical expertise, patient preferences and conditions,

available resources, as well as the judgment and qualifications

of the nurse [12]. Besides the widely held view that EBP leads

to high quality care and the best patient outcomes [9], experts

assert that EBP also reduces practice variations, promotes

consistency of care, enhances patient safety, increases self-care

capacity and improves provider satisfaction [13,14]. At a

system and organizational level, EBP has been shown to improve

cost-effectiveness [15].

2.3 Methodological Framework

The CAN-Implement adaptation and implementation planning resource

version-3 was the overarching framework used to critique and

assess the relevance of the two North American ostomy guidelines,

to the Middle East [7]. This comprehensive framework comprises

3 phases: (1) problem identification; (2) solution building

and (3) implementation, evaluation & sustainability. It

is structured around 9 sequential steps, each designed to

assist users to evaluate, adapt and implement guidelines at

the point-of-care. Each step consists of specific activities

associated with the evaluation of existing practice guidelines

and includes strategies for making decisions about their relevance

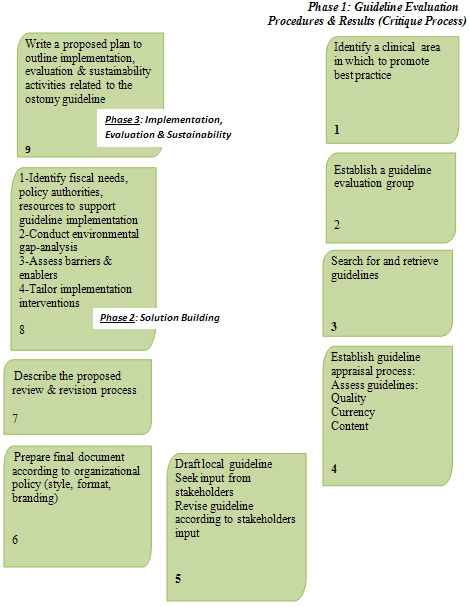

to local contexts (Figure 1).

Figure 1: CAN-Implement Guideline Adaptation and Implementation

Planning Resource

Adapted

from Harrison, M. & van den Hoek, J. (2012). Canadian

Guideline Adaptation Study Group. CAN-IMPLEMENT: A Guideline

Adaptation and Implementation Planning Resource. Queen's University

School of Nursing and Canadian Partnership Against Cancer,

Kingston, Ontario, Canada. Adapted

from Harrison, M. & van den Hoek, J. (2012). Canadian

Guideline Adaptation Study Group. CAN-IMPLEMENT: A Guideline

Adaptation and Implementation Planning Resource. Queen's University

School of Nursing and Canadian Partnership Against Cancer,

Kingston, Ontario, Canada.

2.3.1 Critiquing Process -- CAN-Implement Phase 1

Phase 1 of the CAN-Implement framework consists of 7 steps.

The initial four steps involve the following activities: (1)

identifying a clinical best practice target; (2) establishing

an interprofessional team who will participate in the evaluation;

(3) describing the strategies to locate existing guidelines;

and (4) clarifying the processes, as well as criteria for

appraising the guidelines. Activities of steps 5-7 entail

seeking input from stakeholders and/or opinion leaders, drafting

a document to reflect the consensus of evaluation team members

and outlining the plan for on-going reviews and revision processes.

These final 2 steps focus on: (1) identifying policies, stakeholders,

resources and an implementation plan and (2) assessing the

clinical environment for barriers and facilitators that may

influence guideline use, specifying implementation interventions,

as well as evaluation and sustainability strategies.

3. Results of Phase 1 Critique

3.1 Practice Guideline Target

As noted in the introduction, no practice guidelines for ostomy

care are currently in use in the Arabian Gulf region. To reduce

practice variation and to ensure optimal standards of care

and patient outcomes, a practice guideline was deemed necessary.

The largest health care corporation serving the major population

of Qatar was the target site for this project. In 2013, over

50 new stoma surgeries were performed at this large tertiary

care center.

3.2 Guideline Evaluation Group Formed

Led by the graduate nursing student, a guideline evaluation

group was formed. The team consisted of the student's academic

supervisor as well as clinical experts, including the physician

lead for colorectal cancer services and two advanced clinical

nurse specialists (ANCSs) in the GI program.

3.3 International Ostomy Care Guidelines Located

A literature search uncovered a Canadian ostomy care and management

guideline published by the Registered Nurses Association of

Ontario (RNAO) [16] and an American practice guideline for

fecal ostomy developed by the Wound, Ostomy and Continence

Nurses Society (WOCN) [17]. From the Association of coloproctology

of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI) and the Scottish Intercollegiate

Guidelines Network (SIGN), sixteen colorectal guidelines were

found; however, none were relevant to stoma care or management.

Scrutiny of other data bases, including the World Health Organization

(WHO) Guidelines, National Institute for Clinical Excellence

(NICE) Clinical Guidelines, National Cancer Care Network (NCCN),

Royal College of Nursing, Cumulative Index to Nursing &

Allied Health (CINAHL), Pub Med and Google Scholar, resulted

in no guidelines related to ostomy care. The two guidelines

from RNAO and WOCN were the focus of critique in this project.

3.4 Guideline Appraisal Process Established

3.4.1 Instruments

Literature indicates the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research

and Evaluation (AGREE II) instrument is the universally recognized

gold standard for evaluating practice guidelines [18]. The

AGREE II tool has been translated into 32 languages and is

employed widely to assess the quality of guidelines. The World

Health Organization, the Council of Europe and the Guidelines

International Network recommend this tool for guideline appraisal.

The AGREE II instrument consists of 23 Likert scale items

grouped into six domains. These include: scope and purpose,

stakeholder involvement, rigor of development, clarity and

presentation, applicability, and editorial independence [19].

Domain scores are influenced by the degree to which the guideline

development processes are described and the strategies used

to reach agreement about recommendations for practice [20].

Besides generating separate quality scores in each domain,

the AGREE II instrument enables the appraiser to assign an

overall quality rating of the guideline. This global score

indicates whether the guideline is accepted for use in practice

(e.g. adopted without modification, adopted with alteration(s)

or not adopted). Field testing of the AGREE instrument has

shown acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha .64

to .88) [19].

An additional tool, the Rapid Critical Appraisal (RCA) Checklist

for Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines [21] was also

used in the guideline review process. Scoring criteria for

this 17-item checklist are grouped into three quality domains:

credibility, applicability and generalizability. Two items

unique to this brief checklist addressed practice relevance

which had not been covered in the AGREE II instrument. As

such it offered an enhancement to the AGREE II tool. No publications

reporting validity/reliability testing of the RCA tool could

be found.

Consultation with the primary author at Ohio State University

in USA confirmed the tool has not undergone psychometric testing

(email communication B. Melynk, Dec. 13, 2014).

3.4.2 First Level Critique

An independent appraisal of each guideline using the two standardized

tools was completed by the graduate nursing student. This

was followed by an inter-rater reliability check by the academic

supervisor. Revisions were made and results of this first-level

analysis were then shared with the two ACNSs on the evaluation

team. Rather than completing a comprehensive independent critique,

ACNSs reviewed the initial critique, offered recommendations

about the guideline quality, relevance and content and gave

input about resources and ostomy care issues specific to Qatar.

3.4.3 Second Level Critique

In the ensuing 2nd level analysis, data from the individual

critique of RNAO and WOCN guidelines were synthesized by the

graduate nursing student and used to inform the recommendation

to adopt or adapt elements of one or both guidelines. Strengths

and weaknesses of each guideline were appraised specific to

content, relevance and quality. A composite summary was created

structured around the domains of AGREE II tool [18].

3.5 Recommendation to Adapt Guideline

Adopting a guideline means accepting all of its content, including

recommendations [22]. However, if all of the content or recommendations

in the guideline are not considered relevant to local contexts,

the evaluation team selects information considered applicable

and reformats it into a new guideline. This is the process

of adapting guidelines [22]. Following review and appraisal

of both RNAO and WOCN guidelines, a recommendation was made

to adopt with revision (adapt), the RNAO best practice guideline

(BPG) on ostomy care and management and to adopt select parts

of the WOCN guideline.

3.6 Local Guideline Drafted

Following the comprehensive review and critique of the Canadian

and American guidelines [16, 17], the graduate student, acting

as project lead, recommended adaptation of the RNAO guideline

with additions from the WOCN guideline for use in Qatar. The

revised guideline included 19 of 26 recommendations from the

RNAO guideline and the pre-operative ostomy education component

from the WOCN.

3.7 Input from Internal Stakeholders Obtained

As recommended by the CAN-implement authors [7], the adapted

BPG was presented to internal stakeholders on the guideline

evaluation team for their input and approval. Besides obtaining

the perspective of the two ACNSs and senior colorectal-oncology

surgeon, advice from clinical pharmacologists was sought.

Pharmacists suggested including the generic name, along with

the medication category, in the medication flow sheet to ensure

patient understanding. Other suggestions included: (1) eliminating

sensitive information from the sexual information sheet to

avoid cultural inappropriateness; (2) presenting nutritional

management tips in user-friendly language to ensure information

is understandable to users; and (3) translating the patient

information sheets to local languages to be useful to consumers.

3.8 Guideline Revised According to Stakeholder Input

Feedback from internal stakeholders was incorporated into

the final guideline adaptation. Final approval to proceed

with the implementation of the proposed guideline into local

practice was received from the clinical lead of colorectal

services and ACNSs.

3.9 Final Document Prepared According to Policy

Preparing the final document for internal use in local contexts

required consideration of style, format and branding issues

to ensure a standardized appearance with other practice guidelines

(BPGs) in the organization.

3.10 Review and Revision Process of Local Guideline Specified

Organizational policy and procedure specific to each health

care centre will inform decisions about revision processes.

For instance, the organization targeted for ostomy BPG implementation

requires that guidelines be reviewed every three years or

earlier if new evidence is published, a problem is identified

or there is a change in operational, administrative or clinical

practice. The graduate student (now employed as an ACNS in

the organization), will regularly monitor internal, local,

regional and international practices. She will also be on

the lookout for new clinical practice guidelines, systematic

reviews and randomized controlled trials pertaining to ostomy

care and management. Continuing consultation with internal

and external experts in ostomy and colorectal cancer care

will be essential to ensure the most current evidence from

new studies, grey literature and/or unpublished trials is

considered in guideline revisions [10].

4. Discussion

4.1 Ostomy Guideline Implementation in the GCC Health System

Context

Having completed the phase 1 critique of two international

guidelines, the next steps in the CAN-Implement model, namely,

phase 2 solution building and phase 3 implementation, evaluation

and sustainability, require attention to local contextual

variables that influence use of the adapted guideline. Priority

activities focus on assessing the organizational and cultural

context into which the guideline will be introduced.

4.1.1 Organizational Challenges and Opportunities

Careful analysis of organizational policies, stakeholder involvement

and resource implications need to be considered before guideline

implementation and evaluation can proceed. At the health care

corporation in Qatar targeted for guideline implementation,

policy approval must be obtained from the quality management

department and corporate policy chapter committees (CPCCs).

Final decision-making authority regarding the introduction

of any proposed guideline (whether new or revised) resides

with these bodies. Following signed approval of the CPCC lead

officer, the proposed guideline is then submitted to the regulatory,

accreditation and compliance services (RACS). At this level,

a corporate memo is generated confirming the guideline meets

standardized criteria. It is then forwarded to the Chief Executive

Officer of the organization where final sanction is obtained

before posting on the hospital intranet. These policies are

intended to ensure consistent practice regarding guideline

approval processes in the organization.

The involvement of clinical experts, opinion leaders and relevant

internal stakeholders is critical in all phases of the guideline

implementation and evaluation process. Input and expert knowledge

of two clinical nurse specialists, two clinical pharmacists

and a surgeon from the colorectal team helped to ensure guideline

content and implementation - evaluation plans were realistic

and practical. External personnel with expert knowledge of

ostomy care and implementation science were identified who

could provide problem-solving assistance or consultative guidance

as required. Throughout this initiative, liaison occurred

between the graduate nursing student and international experts

whose resource materials had guided each stage of the project

[7, 16, 17].

A budgetary plan specifying implementation and evaluation

expenses is integral to any guideline project. This will require

consideration of production, distribution, marketing, education

and evaluation costs. To promote fiscal responsibility, existing

human resources in the organization were identified to support

the implementation and evaluation of the adapted ostomy guideline.

For instance, nurse educators will be involved in teaching

staff on the two surgical floors, surgical intensive care

unit (SICU) and operating theatre where most of the ostomy

care is provided. The initial training will be delivered in

a four-hour intensive workshop. Staffing needs in these units

may need to be temporarily increased until the education of

all nurses is complete. An evidence-based practice champion

(EBPC) on each unit will be identified, who possesses excellent

interpersonal skills and knowledge competencies specific to

ostomy care. EBPCs will attend a one-day intensive workshop

to prepare them to act as unit-based resources. This "train-the-trainer"

approach [23] is intended to promote effective resource utilization,

as well as staff engagement in the change process. The graduate

student (now ACNS) will act as resource to EBPCs who are assuming

a leadership and mentoring role in supporting the implementation

of the ostomy guideline at the unit level. Recognition and

feedback to EBPCs is deemed important at this early stage

of guideline implementation as it represents the movement

towards a culture of evidence-based practice.

4.1.2 Gap Analysis

After policy, stakeholder and resource issues have been considered,

experts suggest an internal gap analysis be conducted to clarify

what and how much needs to be changed in existing practices

and systems to support effective guideline implementation

[7]. A gap analysis involves assessing the degree of congruence

between current ostomy care practices and guideline recommendations.

Practice variations related to ostomy care uncovered in the

analysis will inform planning decisions regarding practice

change, educational content, implementation strategies and

timelines. On the other hand, current ostomy practices that

are consistent with the guideline will be the focus of positive

feedback.

In the preliminary gap analysis, the project lead noted that

nurses working in the four units treating patients with stoma

do not all have knowledge of ostomy risk factors and peristomal

complications. This will become part of the educational content

during the guideline training. The gap analysis also uncovered

variance between current professional practice and recommendations

related to colostomy irrigation and use of suppositories.

This content will also be incorporated into the guideline

training.

Besides identifying professional practice variance, an organizational

gap analysis may also uncover deficiencies related to resources

and/or health system capacity. For example, a resource issue

apparent in this project was related to the heavy workload

of the two ACNSs in the GI and colorectal cancer program.

Both provide the ostomy care support in the organization and

both have similar roles to that of Enterostomal Therapy Nurses

(ETNs). Their role begins pre-operatively and continues throughout

the post-operative and follow-up phase of the patient's care

trajectory. A future consideration may be to delegate ostomy

care to the wound care team or to hire certified ETNs. Whoever

performs the role of ostomy specialist assumes responsibility

for ensuring high standards of ostomy care through consultation,

education, collaboration and team coordination in order to

promote consistency and continuity of care amongst all multidiscipline

staff.

With respect to health system capacity, limited information

is available about the role of home care services in Qatar

related to the post-discharge needs of new ostomy patients.

This gap, related to care continuity following hospitalization,

represents an important area for further exploration and improvement.

As the change process evolves, it will be important to identify

facilitators and enablers likely to foster implementation

success. Understanding barriers will enable the team to plan

effective strategies to address obstacles that might interfere

with effective implementation. Recognizing facilitators will

provide insight about the forces likely to result in successful

implementation [7]. The implementation strategy for the ostomy

care and management guideline for local use will be informed

by data obtained from the steps previously described. That

is, input from project advisors, budgetary planning, resource

availability and unit-based gap analysis, as well as barriers

and enablers will shape implementation decisions.

4.1.3 Evaluation/Monitoring

Evaluating the effective use of new guidelines requires consideration

of organizational capacity, resource needs and monitoring

strategies. To assess the outcomes of the ostomy guideline

implementation in the Qatar health care corporation, clinical

observations and monitoring activities will be used to evaluate

nurses' compliance with the guideline and skill competencies

related to stoma care. Patient outcomes, as assessed by indicators

such as stoma complications, infection and readmission rates,

will also be monitored, even though it is acknowledged that

direct cause-effect inferences cannot be confirmed between

nurses' compliance with the guideline and these outcome indicators.

Process variables associated with the evaluation of the education

phase of the guideline implementation may include: (1) number

of staff who attended the training sessions; (2) number of

units involved in the training; (3) hours spent in training

sessions; and (4) resources used in the training process.

Outcome variables that will be assessed related to the education

include: (1) staff knowledge and skill related to the guideline

content; (2) guideline utilization and provider compliance

with the standard of care, (3) staff satisfaction with the

teaching/learning process, (4) staff satisfaction with access

to resources during regular hours and after hours.

Other potential evaluation methods could include chart audits,

informal interviews with staff and patients, as well as anecdotal

comments collected in unit log books. These data will provide

baseline information that can be used for comparison over

time. A mechanism will be established to ensure the tracking,

reporting and resolution of problems encountered by staff

and to record gaps in guideline content.

4.1.4 Sustainability

Sustainability of the ostomy practice guideline is at risk

if knowledge contained within it becomes outdated or irrelevant

to current practice and if point-of-care practitioners do

not see the value of integrating best practice principles

into their daily care giving activities. Sustainable change

will be easier to maintain if guidelines are embedded into

electronic documentation and decision supports within the

organization [24]. The project lead (entry level ACNS) will

explore how the ostomy guideline can be linked with the clinical

information system currently being implemented in the corporation.

4.2 Ostomy Guideline Implementation in the GCC Cultural

Context

As noted previously, rates of colorectal cancer are increasing

in Qatar [25, 26] and clinician interest in standardizing

treatment practices has become a national priority [2, 9,

27]. Besides considering the health system context, guideline

implementation must consider the demographic, cultural and

religious context into which the guideline is introduced.

4.2.1 Cultural Challenges and Opportunities

The total population in Qatar is just under 2.5 million [28].

About 80% live in the capital city of Doha and another 10%

live in other urban areas of the country [29]. Population

demographics reflect a diverse cultural mix. Arab nationals

(approximately 0.3 million) comprise less than 15% of the

population. The vast majority of the population consists of

expatriates from multiple countries. Indians and Nepalese

represent the largest groups (1 million combined) and Filipinos

and Egyptians (0.4 million combined) are the other most prevalent

cultural groups.

Over 75% of people living in Qatar practice the Islamic faith;

there is a mix of Arab and non-Arab Muslims. Christians (8.5

- 10%) and other religions, such as Hinduism and Buddhism

make up the remaining population. Similar to neighboring GCC

countries, Qatar has a high proportion of young male construction

workers from low income countries in the Eastern Mediterranean,

South-East Asia, Western Pacific and African regions. As a

result, there is a disproportionate male:female ratio (75:25)

[28].

As Islam is the dominant religion in this culturally diverse

country, a challenge for health professionals is to understand

how culture and religion influence health, self-concept and

response to illness. Authors note that spiritual affiliation

and strength of faith are basic elements of one's cultural

identity [30]. Though there is abundant research describing

the cultural and religious aspects of caring for Muslim patients

[31, 32, 33, 34, 35], there is scarce evidence describing

Muslim patients' stressors and responses to stoma surgery.

In multicultural, Muslim societies such as Qatar, the provision

of culturally competent care requires that health professionals

provide individualized, holistic care that attends to the

spiritual, cultural, psychosocial, interpersonal and clinical

needs of all persons [35]. Cultural competence involves integrating

cognitive and affective components essential for establishing

culturally-relevant relationships between patients and providers

[36].

The preliminary gap analysis completed for this local guideline

adaptation project, revealed that health care providers, including

staff nurses and physicians, do not consistently perform comprehensive

patient/family assessments on persons with ostomy. The focus

of assessment tends to be on physical aspects of care (e.g.

stoma site, signs and symptoms). Less attention is directed

to psychosocial, sexual, cultural, spiritual, and religious

assessment. Dieticians, pharmacists, physiotherapists and

social workers are not regularly involved in patient consultation.

Project team members recognized that these disciplines should

become part of the colorectal team.

Gap analysis also revealed that all patients may not receive

similar information in the pre-operative phase of care. For

instance, those who do not speak one of the dominant languages

(Arabic or English) may miss formal pre-op education. Self-care

practices related to ostomy management may vary within and

between cultural groups or religions. Evaluation measures

have not been formalized to assess patient/family understanding

of self care practices that ensure safe, proficient use of

ostomy products and appliances. These issues represent targets

for improvement.

Beyond cultural and spiritual factors, other demographic variables

challenge the provision of culturally competent care. For

instance, language, income and education level are crucial

issues to assess in Qatar since a large proportion of the

population are migrant workers who do not speak Arabic or

English. This may impede the ability of professionals to communicate

and deliver consistent information to all patients. Culturally

appropriate services (education, counselling, resources, supports)

that consider language and literacy levels must be thoughtfully

planned and customized for patients and families. Studies

of expatriate workers in Kuwait with cancer revealed that

language negatively impacted the adequacy of oncology care

for both Arab-speaking and non-Arab speaking patients. This

relates to the fact that, similar to Qatar and other GCC countries,

many expatriate health care professionals do not speak Arabic

or other languages of patients [37, 38].

Literature indicates the main challenges specific to ostomy

care and religious beliefs of Muslims evolve around hygiene

and prayer, gender and modesty, as well as sexuality and body

image. Following stoma surgery, the individual's body image

and/or self esteem may be altered; perceptions of attractiveness

may have changed and feelings about sexuality may be negatively

impacted [16,39]. These issues may be particularly relevant

for women, owing to the ideals that society places on them

to reflect a positive sexuality and attractive body image

[40]. A Jordan study of Muslim women experiencing bodily changes

during critical illness distinguished three areas of patient

concern: the physical body, the social body and the cultural

body [41]. Jordanian women's dependence on health professionals

for physical care was perceived as reduced performance and

bodily strength which triggered feelings of shame, burden

and helplessness. An altered physical condition was seen by

the women as an inability to contribute normally to family

role functions which induced feelings of social inadequacy.

Female Muslim participants also viewed physical illness as

a threat to their cultural identity due to Islamic beliefs,

customs and expectations regarding women's role in the family

and community.

Having an ostomy forces an individual of the Islamic faith

to confront and adapt to issues pertaining to religious customs.

For Muslims, stoma formation may interfere with their daily

prayer rituals. They must ensure the cleanliness of their

clothes, physical body and place of prayer (5 times / day);

the practice of washing [ablution] prior to prayer, after

sexual intercourse, urination and defecation is rooted in

Islamic ideology [42]. Muslim patients with ostomy may experience

spiritual conflict, not only by the sight of bodily fluids,

but by the perception that they are "unclean".

Research has documented that Muslim patients with stoma report

a more negative quality of life than non-Muslim patients.

This has been attributed to their cessation of daily washing

rituals, mosque visits and prayers. Study participants conveyed

that physiologic factors, such as uncontrolled flatus and

visible faeces, resulted in their inability and/or unwillingness

to observe normal religious customs specific to prayer. As

a result, they experienced social isolation and decreased

quality of life [42]. This reinforces that Muslem patients

with ostomy face unique cultural and religious challenges

that may induce intense conflict and stress. Guideline content

must include comprehensive assessment, as well as resources

and services to address the unique psychosocial and spiritual

support needs of patients.

Privacy, modesty and dignity issues, important to all people

regardless of culture or religion, may have special significance

to Muslim patients with ostomy. Muslim custom related to modesty

requires that clothing cover the entire body, neck and head

and must not be tight, sheer or unduly conspicuous. Muslim

apparel and adherence to modest dress standards may be a source

of comfort to a person with ostomy, serving to limit public

scrutiny or perceived exposure of his/her altered physical

body. Islamic modesty rules also place restrictions on privacy,

the mention of bodily functions and gender relationships [43].

For example, direct eye contact with the opposite sex outside

the family is forbidden for some Muslims and same-sex medical

care providers are generally preferred.

Islamic tradition posits that one's privacy is integral to

his/her dignity [44]. Evidence indicates that "Muslim

women specifically and Arab women in general do not tolerate

unnecessary exposure of their bodies" [45]. Externalizing

the bowel may have a devastating impact on a Muslim woman's

self-image and personal sense of dignity. Because it is not

customary for people of the Muslim faith to discuss sensitive

issues related to bodily functions [43, 46], psychological,

social, and religious supports should be available to assist

individuals to disclose feelings about altered body image

following stoma surgery [39]. On the other hand, research

has shown that strong religious affiliation can have a positive

effect on body image, possibly by redirecting judgments about

self-worth away from appearance and towards moral and ritualistic

pursuits relevant to an individuals' faith [47]. The 21 countries

in the Eastern Mediterranean Health Region [48] are Muslim-dominant

societies. However, varied geo-political, economic and social

factors, coupled with demographic diversity, make it impossible

to predict with certainty whether an ostomy guideline adapted

in Qatar will be relevant to the entire Middle East region.

To assess the relevance of the Qatar ostomy guideline to other

areas of the Middle East, clinical stakeholders in those countries

should engage in a collaborative interdisciplinary appraisal

process similar to that described in this paper. Because Qatar

is the first GCC state to take lead in developing and implementing

guidelines for ostomy care, this small Arabian Gulf country

may become a centre of excellence for best practice in this

field, possibly attracting the attention of neighboring countries.

We envision that the introduction of an ostomy care and management

guideline in Qatar for use by nursing and allied health professionals

will be complementary to the medical guideline for colorectal

cancer available through the National Institute for Health

and Care Excellence (NICE) that serves as a practice standard

for GCC and Middle East colorectal surgeons [49]. Integration

of both guidelines is expected to be the beginning of a new

era of best practice for colorectal cancer and ostomy care

consistent with the national vision to create a world class

health system [27].

5. Conclusion:

Experts all agree that clinical practice guidelines developed

in one part of the world may be difficult to implement in

another geographic region. This paper has summarized the systematic

steps involved in appraising the quality, content and relevance

of two different ostomy guidelines developed in North America

to the Middle East context. The goal was to produce a guideline

for use by health care professionals employed in one major

health corporation in the GCC state of Qatar. The process

involved systematic procedures, standardized critiquing instruments

and input from interprofessional team members. The initiative

enabled a graduate nursing student to assert her leadership

by actively liaising with international experts in EBP, BPGs

and ostomy care. It also provided an opportunity for her to

engage locally with interprofessional colleagues and to involve

them in decision-making to define and shape best practice.

The ultimate goal was to ensure a practice guideline exists

to foster the delivery of quality care to patients with ostomy.

The resultant guideline adaptation is expected to support

optimal health outcomes, healthy adjustment, effective self-care

abilities, bio-psycho-social-spiritual well-being and a positive

quality of life, thereby helping patients face the challenges

of living with ostomy with confidence and independence. The

adapted ostomy care and management guideline is intended for

use by staff involved in care of patients in the preoperative,

postoperative and rehabilitation period. Completing implementation

and evaluation of this guideline in the local context is the

next immediate step. A future priority will be to assess the

need for patient-specific ostomy guidelines.

Acknowledgement

S. Abdul Qader is a new MN graduate working as a clinical

nurse specialist in the colorectal program at Hamad Medical

Corporation in Doha, Qatar.

M.L. King is assistant professor in the faculty of nursing

at University of Calgary in Qatar.

References

[1] Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S,

Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer Incidence

and Mortality Worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns

in GLOBECAN 2012. International Journal of Cancer 2014 October;

136(5): E359-386.

[2] Icli F, Akbulut H, Bazarbashi S. Kuzu MA, Mallath, MK,

Rasul KI, Strong S. Syed AA, Zorlu F. Engstrom PF. Modification

and implementation of NCCN guidelines on colon cancer in the

Middle East and North Africa region. Journal of The National

Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2010 July; (8):S22 - S25.

[3] Rasul K, Awidi A, Mubarak A, Al Homsi, U. Study of colorectal

cancer in Qatar, Saudi Medical Journal. 2001 August; (22):705-707.

[4] Wu H, Chau J, Twinn S. Self-efficacy and quality of life

among stoma patients in Hong Kong. Cancer Nursing. 2007 May;

30(3):186-193.

[5] Burch J. Stoma care in the community. British Journal

Of Community Nursing. 2014 August; 19(8):396-400.

[6] Field M, Lohr K. Guidelines for clinical practice: From

development to use. National Academy Press.Washington:DC;

1992.

[7] Harrison M, van den Hoek J. Canadian Guideline Adaptation

Study Group. CAN-IMPLEMENT: A guideline adaptation and implementation

planning resource. Queen's University School of Nursing and

Canadian Partnership against Cancer, Kingston, Ontario, Canada;

2012.

[8] Locatelli F, Andrulli S, Del Vecchio L. Difficulties of

implementing clinical guidelines in medical practice. Nephrol.

Dial. Transplant. 2000 September; (15), pp. 1284-1287.

[9] Jazieh A, Azim H, McClure J, Jahanzeb, M. The Abu Dhabi

Declaration: The process of NCCN guidelines adaptation in

the Middle East and North Africa region. Journal of the National

Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2010 March; 8 (S3): S2-4

[10] Harrison M, Légaré F, Graham I, Fervers

B. Adapting clinical practice guidelines to local context

and assessing barriers to their use. CMAJ: Canadian Medical

Association Journal. 2010 February; 182(2):E78-84.

[11] Sackett D, Rosenberg W, Gray J, Haynes R, Richardson

W. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't.

Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research. 2007 February;

455:3-5.

[12] Cullum N, Ciliska D, Haynes B, Marks S. Evidence-based

Nursing: An Introduction. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing;

2008.

[13] Wells N, Free M, Adams R. Nursing research internship:

enhancing evidence-based practice among staff nurses. Journal

of Nursing Administration. 2007 March; 37(3):135-143.

[14] Novak D, Dooley S, Clark R. Best practices: understanding

nurses' perspectives. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2008

October; 38(10):448-453.

[15] Winch S, Creedy D, Chaboyer W. Governing nursing conduct:

the rise of evidence-based practice. Nursing Inquiry. 2002

September; 9(3):156-161.

[16] Registered Nurses' Association of Ontario (RNAO), Ostomy

Care and Management, RNAO: Toronto, ON; 2009.

[17] Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nurses Society (WOCNS).

Management of the patient with a fecal ostomy: best practice

guideline for clinicians, WOCNS: Mount Laurel, New Jersey;

2010.

[18] The AGREE II Collaboration, Appraisal of guidelines for

research and evaluation: AGREE II instrument. 2009. http://www.agreetrust.org.

[19] Burgers J, Fervers B, Cluzeau F, et al. International

assessment of the quality of clinical practice guidelines

in oncology using the Appraisal of Guidelines and Research

and Evaluation Instrument. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004

May; 22(10):2000-2007.

[20] Graham I, Harrison M. EBN users' guide. Evaluation and

adaptation of clinical practice guidelines. Evidence Based

Nursing. 2005 July; 8(3):68-72.

[21] Melnyk B, Fineout-Overholt E. 2nd ed. Evidence based

practice in nursing & health care. A guide to best practice.

Wolters Kluwer Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia,

PA; 2011.

[22] Groot P, Hommersom A, Lucas P. Adaptation of clinical

practice guidelines. Studies in Health Technology & Informatics.

2008 September; 139:121-139.

[23] Kalisch B, Boqin X, Ronis D. Train-the-trainer intervention

to increase nursing teamwork and decrease missed nursing care

in acute care patient units. Nursing Research. 2013 December;

62(6), 405-413. doi:10.1097/NNR.0b013e3182a7a15d

[24] Dowding D. Computerized decision support systems in nursing.

Cullum N et al. Evidence-based nursing: An Introduction. Oxford:

Blackwell Publishing; 2008.

[25] Bar-Chana M, Ibrahim AS, Mikhail N. MOS Epidemiology

Group Special Report: cancer incidence in Mediterranean populations.

Mediterranean Oncology Society, 2009 http://www.mosoncology.org/index.php/literature

[26] Bener A, Ayub H, Kakil R, Ibrahim W. Patterns of cancer

incidence among the population of Qatar: a worldwide comparative

study. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 2007 8(9),19-24.

[27] Brown R, Kerr, K. Haoudi, A. Darzi, A. Tackling cancer

burden in the Middle East: Qatar as an example. The Lancet

2012 November, 13: 2501-e508. www.thelancet.com/oncology

[28] Qatar's Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics.

[Internet]. Qatar, 2014.[ updated December July 2014]. Available

from: http://www.bqdoha.com/2013/12/population-qatar

[29] Agy SN. Countries and their cultures [Internet]. Qatar,

2015. Available from: http://www.everyculture.com/No-Sa/Qatar.html.

[30] Tarakeshwar N, Stanton J, Pargament K. Religion: An overlooked

dimension in cross-cultural psychology. Journal of Cross-cultural

Psychology.2003 July ;34, 377-394.

[31] Marrone S. Factors that influence critical care nurses'

intentions to provide culturally congruent care to Arab Muslims.

Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2008 January ;19(1), 8-15.

[32] Simpson J, Carter K. Muslim women's experiences with

health care providers in a rural area of the United States.

Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2008 January ;19(1), 16-23.

[33]Al-Shahri M.Z. Culturally Sensitive Caring for Saudi Patients.

Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2002 April ;13 (2), 133-138.

[34]Yousef A. Health beliefs, practice, and priorities for

health care of Arab Muslims in the United States: Implications

for nursing care. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2008 July;19(3),

284-291.

[35] Lovering S. (2012). The Crescent of Care: a nursing model

to guide the care of Arab Muslim patients. Diversity and Equality

in Health and Care. 2012 September; 9,171-178

[36] Alexander GR. Cultural competence models in nursing,

Nursing Clinics of North America. 2008 December; 20(4): 415-421.

[37] Alshemmari SH, Refaat S, Elbashmi AA, AlSirafy S. Representation

of Expatriates Among Cancer Patients in Kuwait and the Need

for Culturally-Competent Care. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology

2012 30: 380-385.

[38] Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM, Guadagnoli E, Fuchs CS, Yost

KJ, Creech, CM, . . . Wright, WE. Patients' perceptions of

quality of care for colorectal cancer by race, ethnicity,

and language. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2005 23: 6576-6586.

[39] Kuzu MA , Topçu O, Uçar K, Ulukent S, Unal

E, Erverdi N, Elhan A, Demirci S. Effect of sphincter-sacrificing

surgery for rectal carcinoma on quality of life in Muslim

patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002 October;45(10):1359-66

[40] Grogan S. Body Image: Understanding Body Dissatisfaction

in Men, Women and Children. 2nd ed. Routledge, New York; 2008.

[41] Zeilani R, Seymour JE. Muslim Women's Narratives About

Bodily Change and Care During Critical Illness: A Qualitative

Study. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2012 December ; 44

(1), 99-107.

[42] Black P. Understanding religious beliefs of patients

needing a stoma. Gastrointestinal Nursing. 2011December; 9(10):17-22.

[43] Rashidi A, Rajaram SS. Middle Eastern Asian Islamic women

and breast self-examination: needs assessment. Cancer Nursing.

2000 February;23, 64-70.

[44] Kamali MH. The Dignity of Man: An Islamic Perspective.

Cambridge, England: The Islamic Texts Society.2002.

[45] Hammoud MM, White, CB, Fetters MD. Opening cultural doors:

Providing culturally sensitive healthcare to Arab American

and American Muslim patients. American Journal of Obstetrics

and Gynecology. 2005 October ;193, 1307-11.

[46] Andrews CS. Modesty and healthcare for women: understanding

cultural sensitivities. Community Oncology.2006 July; 3 (7):

443-446.

[47] Ferraro KF. Firm believers? Religion, body weight, and

well-being. Review of Religious Research. 1998 March ;39,

224-244.

[48] World Health Organization. Countries [Internet]. 2011.

Available from: http://who.net/countries/en/.

[49] National Institute for Health and Quality Excellence

(NHS). The diagnosis and management of colorectal cancer -

NICE quality standard 131. 2014 December: 1-50. Available

from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg131.

|

|