| |

April

2015

- Volume 9, Issue 2

Evidence Based Practice: Aerobic Exercise and Major Depressive

Disorder

|

( (

|

Yousef Qan`ir

Correspondence:

Yousef A. Qan'ir,

M.Sc., RN

Master Degree in Nursing

The Hashemite University

Zarqa, Jordan

P.O. Box 150459, Zarqa 13115,

Jordan

Email: Yousefqaneer@hotmail.com

|

|

|

Abstract

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is one of the common

health problems, and is estimated to affect 121 million

adults worldwide. MDD is a recurrent illness, with high

incidence of returning, and the risk of relapse that

increases as the number of previous episodes increase.

Hence, the choice of treatment is important to improve

the quality of life and to prevent or minimize recurrent

episodes. Physical exercise is an example of alternative

and complementary therapy that has received considerable

and significant attention in the treatment of MDD. The

efficacy of aerobic exercise approaches is considered

and has a place in mental health practice. According

to many studies aerobic exercise is the preferred form

of exercise for patients with MDD. Moreover, Aerobic

exercise has been proven as an effective treatment for

MDD, and there are sufficient studies to help health

care providers to prescribe aerobic exercise as a treatment

choice for MDD patients. It is recommended that patients

participate in three to five exercise sessions per week,

for 30 to 45 minutes per session. Within the range of

intensity for aerobic exercise, that achieves a level

of heart rate of 70 to 85 % of the heart rate reserve.

Furthermore, the majority of research emphasizes that

the exercise regimen should be continued for at least

10 to 16 weeks to achieve the greatest antidepressant

effect.

Key words: Aerobic Exercise; Major Depression.

|

Introduction

Mental health problems are international challenges that have

a significant contribution in illness burden over the entire

world (Blake, 2012). Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is one

of the common health problems, and is estimated to affect

121 million adults worldwide (World Health Organization [WHO],

2012). Projections for the year 2030 indicate that MDD will

rank second only to coronary heart disease as a cause of illness

burden over the entire world (WHO, 2012). Furthermore, WHO,

2012 reported that MDD currently represents a second health

problem regarding disability caused by illness in the world.

MDD is associated with significant morbidity, mortality, and

disability that burden the individual and his family, and

contribute to impaired cognitive skills and deterioration

of the individual life aspects (Blake, 2012; Nahas & Sheikh,

2011). Many risk factors are associated with incidence of

MDD as genetic factors, life events, sleeping disturbance,

alcohol, and some drugs (Townsend, 2011). Symptoms of depression

include feeling of hopelessness and helplessness, loss energy,

anhedonia, agitation, fatigue, withdrawn, weight loss or gain,

fatigue and inappropriate thinking (Townsend, 2011).

MDD is a recurrent illness, with high incidence of returning,

and the risk of relapse increases as the number of previous

episodes increase (Solomon, Keller, Leon, Mueller, & Lvori,

2000). Hence the choice of treatment is important to improve

the quality of life and to prevent or minimize recurrent episodes.

For instance, the majority of western guidelines published

since 2000 have similar recommendations about all stages of

treatment of depression, that is first line treatment is usually

serotonin reuptake inhibitor, psychotherapy, or combination

of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy (Gelenberg, 2010). Indeed,

no single treatment for MDD is effective for every patient

(Nahas & Sheikh, 2011). Almost half of depressed patients

who are treated do not attain full remission of their symptoms

of MDD and they remain under risk of residual symptoms and

relapse (Solomon et al., 2000). Allopathic therapies could

be undesirable options for MDD management illustrated by antidepressant

medications having unpleasant side effect, and psychotherapy

could be time consuming and expensive (Demyttenaere et al.,

2001). Many depressed patients choose complementary alternative

medicine instead of allopathic (Solomon et al., 2000). Hence,

there is a great interest in development of alternative and

complementary therapies to enhance and promote treatment options

of MDD (Blake, 2012).

Physical exercise is an example of alternative and complementary

therapy that has received considerable and significant attention

in treatment of MDD (Blake, 2012). Physical exercise may be

a viable treatment because it can be recommended for any patient

at any time without suffering a negative social stigma (Nahas

& Sheikh, 2011). In general, physical exercise has a significant

and clear positive effect on physical health and psychological

process in the human body (Blake, 2012). Normal physical health

conditions may play a significant role in mental health balance,

and maintain biopsychological aspect in the human body (Helmich

et al., 2010). A number of studies indicated a consistent

association between improving mental health and regular physical

exercise (Hassmen, Koivula, & Uutela, 2000). In addition,

many studies reported that physical exercise might reduce

depressive symptoms in the nonclinical population and in patients

diagnosed with MDD (Nahas & Sheikh, 2011). At the same

time, an association between physical inactivity and higher

levels of depressive symptoms in patients with MDD is observed

(Helmich et al., 2010).

Concept of physical exercise indicates regular, structured,

continuous, rhythmical fashion, and leisure time activity

(Hassmen et al., 2010). Specifically, aerobic exercise is

a kind of exercise which involves prolonged activity of large

muscle groups to produce energy by metabolizing oxygen; such

as running, swimming, and aerobic dancing (Reed & Buck,

2009). Unlike aerobic exercise, anaerobic exercise reflects

intense, brief, and nonsustainable muscular activities that

use the energy to produce activity without inhaling oxygen;

such as in weight lifting, and pushing down (Reed & Buck,

2009).

In fact, the majority of healthy people prefer and use this

kind of exercise in their life activities, and aerobic exercise

is one of the common exercise modalities that is recommended

for mental health improvement (Reed & Buck, 2009). Many

studies have examined its effectiveness and viability to manage

mental disorders (Kanning & Schlicht, 2010). Moreover,

the efficacy of aerobic exercise approaches is considered

and has a place in mental health practice, but some researchers

suggested inconsistent recommendations regarding adoption

of aerobic exercise as treatment choice for MDD (Reed &

Buck, 2009).

Dose, Frequency, and Technique of Aerobic

Exercise for MDD Management

The efficacy of aerobic exercise in treatment of MDD may be

affected by age and severity of symptoms, but intensity of

exercise programs have a substantial impact on aerobic exercise

effectiveness for MDD (Silveira et al., 2013). Determining

the type of exercise for people with MDD has to focus on personal

interest, physical needs, risk for injury, and adverse effects

for current medication. Selecting the convenient exercise

is primary for continued consistent exercise intensity (Silveira

et al., 2013).

In a report of 2013, American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM)

defined many concepts related to intensity of aerobic exercise.

In the beginning, ACSM used heart rate reserve term to reflect

exercise intensity that is equivalent to the desired percentage

of maximal oxygen uptake. Heart rate reserve means the difference

between resting heart rate and maximum heart rate. ACSM set

maximum heart rate as the highest number of beats per minute

during physical exertion, and resting heart rate is the lowest

number of heart beats per minute during ful relaxation and

without distractions. The intended increase in heart rate

reserve means increase in the aerobic exercise intensity (ACSM,

2013). Additionally, ACSM articulated that exercise intensity

reflects how much energy is expended when exercising. ACSM

clarifies a way to optimize energy expenditure by modifying

the intensity of the exercise. It is important to choose mode

of exercise that can be regulated to overload the cardio respiratory

system and increase the heart rate reserve level, so it will

increase exercise intensity (ACSM, 2013).

ACSM (2013) classified exercise mode for MDD treatment regarding

energy expenditure into three groups of exercise (a) exercises

that provide a consistent intensity and energy expenditure

such as walking, jogging, cycling, and stair climbing; (b)

in this group the exercise will burn more calories if a person

worked harder and longer such as aerobic dancing, bench stepping,

and swimming; (c) large muscle contractions with prolonged

activities such as basketball, racquet sports, and volleyball

are high energy expenditure exercise activities. Moreover,

many doses are used to determine energy expenditure in an

aerobic exercise program,for instance, public health dose

of aerobic exercise that is total weekly energy expenditure

of 17.5 kcal/kg/wee k, and low dose aerobic exercise that

is total weekly expenditure of 7 kcal/kg/week (ACSM, 2013).

More energy expenditure means more effective exercise practice

because of the biophysiological actions of muscle contractions,

and hormonal excretion after intensive exercising program

(Drevets, 2001).

Aerobic exercise program for MDD. In their study, Dunn et

al. (2005) reported that aerobic exercise consistent with

public health dose is an effective treatment for MDD, but

a lower dose is comparable to no treatment intervention. Dunn

et al. also concluded that there was no difference in result

between 3 days per week of aerobic exercise and 5 days per

week. Hence, the distinct factor for reduction of MDD symptoms

is total energy expenditure not frequency of exercise sessions.

In the same way, Blumenthal, Smith, and Hoffman (2012) concluded

that no differences between 3 days per week and 5 days per

week of aerobic exercise as a therapeutic exercise regimen

for MDD, but exercise adherence is the essential factor to

profit from the exercise program.

Blumenthal et al. (1999) applied 16 weeks exercise program

of 45 minutes session per day for three days every week on

MDD participants. The result showed positive outcomes after

implementing this method, and the exercise program achieved

therapeutic effects (Blumenthal et al., 1999). Another design,

which is developed by Davidson (2010) within a guideline for

MDD treatment, presented a different aerobic exercise program.

Davidson's program consisted of three times weekly of regular

walking and jogging sessions for 10 weeks; each exercise session

consisted of 10 minutes of stretching exercise, followed by

45 minutes of continuous walking or jogging to obtain desired

exercise intensity by increasing heart to 70-85% of maximum

heart rate of MDD participant. A somewhat distinct aerobic

exercise program performed by Babyak et al. (2000) and Blumenthal

et al. (2007) suggested three exercise sessions per week for

16 consecutive weeks. Every session designate training exercise

ranges equivalent to 70-85 % of heart rate reserve. Each aerobic

session started with 10 minutes warm up period, next followed

by 30 minutes of brisk walking or jogging at intensity consistent

with assigned heart rate reserve. After that, exercise session

concluded with five minutes of cool down exercise. The exercise

program achieved positive results in managing symptoms of

MDD (Babyak et al., 2000; Blumenthal et al., 2007). A positive

outcomes study by Hoffman et al., (2011) applied similar aerobic

exercise method within their randomized clinical trial study

to reduce MDD symptoms. Hoffman et al. designed program of

attending 45 minutes of aerobic exercise of running, jogging,

and treadmill each week for four months within target heart

rate of 70-85% of heart rate reserve.

Briefly, three days of aerobic exercise sessions per week

for consecutive weeks range from 10 to 16 weeks; every session

of jogging, running, walking, or treadmill, or any aerobic

exercise that the patient is interested in, continued for

30 to 45 minutes, and maintained at 70 to 85 % of monitored

heart rate reserve. Also consideration should be given to

the patients` abilities for these exercise sessions in regard

to their health, time, and willingness for exercise practice,

could be an appropriate program for MDD management practice.

PICO Format

Evidence-based practice is integration

of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient

values (Stuart, 2001). To implement evidence based practice

strategies, we can use PICO, which is a method of putting

together a search strategy that allows the health care provider

to take a more evidence-based approach to the literature searching

when searching bibliographic databases (Stuart, 2001).

A clinical question needs to be directly relevant to the patient

or problem. It needs to be phrased in such a way as to facilitate

the search for an answer. PICO makes this process easier (Stuart,

2001). It is a memorial for the important parts of a well-built

clinical question. It also helps formulating the search strategy

by identifying the key concepts that need to be in the article

that addresses the question. A PICO question consists of four

elements (a) population or patients (b) intervention (c) comparison

(d) outcome.

At this level, we can clarify current clinical questions that

articulate the efficacy of aerobic exercise to manage patients

with MDD. Furthermore, it could compare aerobic exercise to

antidepressant in managing MDD. PICO questions apply a convenient

format that will ease process of answering relevant questions.

PICO search strategies will consider the main elements of

PICO questions. Proposed PICO questions elements are illustrated

in Table 1.

Table 1

PICO Questions

Clinical elements are combined through PICO format to formulize

PICO questions. The proposed three PICO questions are:

1- In patients with MDD, does aerobic exercise program

reduce the symptoms of MDD?

2- In patients with MDD, what is the effect of aerobic

exercise program on reducing symptoms of MDD compared to no

aerobic exercise?

3- In patients with MDD, how does aerobic exercise

program compared with antidepressant reduce

symptoms of MDD?

Literature

Review

Effects of Aerobic Exercise on People with MDD

In this situation, one systematic review performed by Phillips,

Kiernan and King (2003) indicated that aerobic exercise has

beneficial effects on patients with MDD, and may increase

social integration, successful adaptation, and self esteem

of patients with MDD. In addition, Phillips et al. (2003)

reported that an aerobic exercise as little as four weeks

could beneficially affect people with MDD. Similarly, Lawlor

and Hopker (2001) in their systematic review concluded that

aerobic exercise may be efficient in reducing symptoms of

depression among patients with MDD in the short term, but

it is not clear for long term treatment plan due lack of follow

up studies.

A number of randomized clinical trials studies examined the

effects of aerobic exercise on people with MDD. For instance,

Carter, Callaghan, Khalil and Morres (2012) found that sufficient

intensity of aerobic exercise has effective outcome on the

depressive symptoms of patients who are experiencing MDD.

Equally, another randomized clinical trial conducted by Dunn,

Trived, Kampert, Clark, and Chambliss (2005) concluded that

standard aerobic exercise is an effective treatment for MDD

of mild to moderate severity. The authors suggested that participants

with MDD who underwent the study showed an improvement in

their mental status after implementing a full aerobic exercise

program (Dunn et al., 2005). In the same way, in 2007, Blumenthal

et al. in their randomized clinical trial study showed that

aerobic exercise program for participants with MDD is better

than no treatment intervention to improve mood status. In

a like manner, one randomized clinical trial reported that

MDD patients positively interested in aerobic exercise, showed

efficacious response after a modest exercise program (Babyak

et al., 2000). Particularly, aerobic exercise is an effective

and potent treatment for patients with MDD in case the patients

are willing to undergo the exercise program (Babyak et al.,

2000). One quasi-experimental study reported that aerobic

exercise program decreased the depression scores in Hamilton

rating scale among elderly women who experienced MDD (Sayyad,

Nazer, ansary, & Khleghi, 2006). Furthermore, in their

pilot study Dimeo, Bauer, Varahram, Proest, and Halter (2001)

concluded that an improvement in mood status could occur after

implementing 10 days of aerobic exercise for patients experiencing

mild MDD.

In contrast, one randomized clinical trial conducted by Krough,

Videbech, Thomsen, Gluud, and Nordentoft (2012) indicated

opposite outcomes to previous studies. Study of Krough et

al. concluded that aerobic exercise has no significant effect

on patients who experienced MDD. Additionally, Krough et al.

reported that duration, frequency, and intensity of aerobic

exercise are not substantial to potentiate aerobic exercise

performance. Another randomized clinical trial showed that

one year of exercise training is not effective for depressive

symptoms among residents of care homes and nursing homes who

are experiencing MDD (Underwood et al., 2013).

Aerobic Exercise versus Antidepressant

Medication

Aerobic exercise may reduce negative side effects of antidepressants,

such as fatigue, dizziness, and constipation, thus increasing

compliance in medication use (Kruisdijk, Hendriksen, Tak,

Beekman, & Rock, 2012). Aerobic exercise could be applied

as a single treatment plan or complementary therapy in addition

to pharmacological treatment (Kruisdijk et al., 2012). No

doubt, adverse effects of aerobic exercise are less than antidepressant,

and aerobic exercise is relatively safer than antidepressant

with low cost charges (Kruisdijk et al., 2012).

One systematic review showed that aerobic exercise and antidepressant

medication are similar regarding reduction of depressive symptoms

on the Hamilton depression rating scale in patients diagnosed

as MDD (Danielsson, Noras, Waern, & Carlsson, 2013). The

same review recommended that people with MDD should be treated

with aerobic exercise instead of antidepressant medication

(Danielsson et al., 2013). Another meta-analysis concluded

aerobic exercise enhances the response to antidepressant treatment

for MDD patients, but it is less effective than antidepressant

treatment in improving MDD symptoms (Silveira et al., 2013).

On other hand, Cooney et al. (2013) concluded in their systematic

review that aerobic exercise is slightly more effective than

no treatment intervention to reduce depressive symptoms among

MDD patients, but is less effective than pharmacological treatment

in reducing depressive symptoms or improving quality of life

for people with MDD.

Another clinical trial study suggested that the effect of

aerobic exercise on MDD remission is similar to antidepressant,

and aerobic exercise may enhance the efficacy of pharmacological

treatment (Hoffman et al., 2011). This conclusion is supported

by another randomized clinical trial conducted by Blumenthal

et al. (2007) who found efficacy of exercise treatment similar

to antidepressant medications, and both treatments are better

than no treatment intervention in patients with MDD. Also,

an earlier study completed by Blumenthal et al. (1999) suggested

more positive expectation regarding aerobic exercise which

may be considered as alternative treatment to antidepressants

to manage MDD. However, some antidepressants may provide rapid

onset therapeutic response more than aerobic exercise that

enhances position of antidepressant medications as the first

line treatment for MDD (Blumenthal et al., 1999).

Discussion

In general, many studies of first level of evidence concluded

that aerobic exercise is effective in reducing symptoms of

patients with MDD. All studies that reported positive outcomes

regarding aerobic exercise efficacy in MDD are summarized

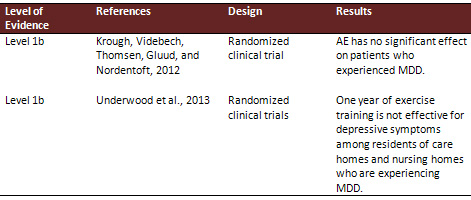

in Table 2. However, as shown in Table 3, two randomized clinical

trial studies showed that aerobic exercise has no effect in

reducing symptoms of MDD. Hence, the clinical questions, which

investigate the efficacy of aerobic exercise and compare it

to no treatment approaches, could be answered after evaluating

all relevant studies.

Click here for Table 2: Summary

of Positive Results Studies for efficacy of AE in MDD

The systematic review and randomized clinical trial studies

articulated a positive relation between aerobic exercise and

reducing symptoms of MDD. High level of evidence in these

studies affords capacity to answer the clinical questions.

No doubt, number and level of evidence of former studies,

that found aerobic exercise is effective in reducing symptoms

of MDD, are more vigorous than studies that showed negative

outcomes.

Searching of literature related to PICO questions that compare

aerobic exercise to antidepressant, found high level of evidence

as represented in Table 4. The studies reported that aerobic

exercise may be similar or less efficient than antidepressant

in reducing symptoms of MDD. However, no studies showed opposite

outcomes. Similarly, aerobic exercise could not be more effective

than antidepressant in reducing symptoms of MDD.

Table 3

Click here for Table 4:

Summary

of Studies for Efficacy of AE versus Antidepressant

Summary

According to former studies aerobic exercise is the preferred

form of exercise for patients with MDD. Moreover, Aerobic

exercise has been proven as an effective treatment for MDD,

and there are sufficient studies to help health care providers

to prescribe aerobic exercise as a treatment choice for MDD

patients. The results showed that patients may experience

a relief in depressive symptoms in as little as four weeks

after starting exercise.

Although a question whether patients with MDD could actually

participate in an aerobic exercise program, the studies suggested

that the majority of MDD patients prefer the aerobic exercise

rather than antidepressant medication and MDD patients drop

out rate from the exercise programs is very low.

It is recommended that patients participating in three to

five exercise sessions per week, for 30 to 45 minutes per

session. Within the range of intensity for aerobic exercise,

that achieves a level of heart rate of 70 to 85 % of the heart

rate reserve. Furthermore, the majority of research emphasizes

that the exercise regimen should be continued for at least

10 to 16 weeks to achieve the greatest antidepressant effect.

The recommended strategies that may help improve adherence

to exercise programs, include asking patients about their

favorite type of exercise, and encouraging them by using a

group exercise program. In addition, it is recommended also

to encourage patients to engage in at least some exercise,

even if they do not exercise enough to meet current public

health dose exercise, they may take a first step in this therapeutic

approach.

It is also recommended more research studies should be carried

out in this area with emphasis on methodological accuracy,

adequate sample size, and follow up research design with long

term examination methods.

Conclusion

Aerobic exercise could be part of the treatment plan for patients

with MDD even as single treatment therapy, or combined with

other allopathic treatment approaches. In addition, the aerobic

exercise program could be implemented as planned and structured

practice according to available randomized clinical trials

methods of aerobic exercise intervention, which reported that

aerobic exercise is effective to treat MDD, and potentiate

antidepressant medications.

Acknowledgement:

The author extend his appreciation to the College of Nursing

at The Hashemite University; specifically to Professor Dr.

Majd Mrayyan.

References

American College of Sports Medicine. (2013). ACSM's guidelines

for exercise testing and prescription for mental disorders.

Retrieved from http://www.acsm.org/about-acsm/media-room/news-

releases/2013/03/13/acsm-to-preview-9th-edition-of-exercise-mental-

guidelines.pdf.

Babyak, M., Blumenthal, J., Herman, S., Khatri, P., Doraiswamy,

P., Moore, K., Craighead, E. (2000). Exercise treatment for

major depression: maintenance of therapeutic benefit at 10

months. Psychosomatic Medicine, 62(3), 633-638.

Blake, H. (2012). Physical activity and exercise in the treatment

of depression. FrontierPsychiatrist, 106(3), 343-352.

Blumenthal, J., Babyak, M., Doraiswamy, M., Watkins, L., Hoffman,

B., Barbour, K.,… Herman, S. (2007). Exercise and pharmacotherapy

in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Psychosomatic

Medicine; 69(7), 587-596, doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e318148c19a.

Blumenthal, J., Babyak, M., Moore, K., Craighead, E., Herman,

S., Khatri, P., Waugh, R. (1999). Effects of exercise training

on older patients with major depression. Archive of Internal

Medicine, 159, 2349-2356.

Blumenthal, J., Smith, P., & Hoffman, B. (2012). Is exercise

a viable treatment for depression. ACSMs Health Fitness Journal,

16(4), 14-21.

Carter, T., Callaghan, P., Khalil, E., & Morres, I. (2012).

The effectiveness of a preferred intensity exercise programme

on the mental health outcomes of young people with depression.

BMC Public Health, 12,187.

Cooney, G., Dwan K, Greig C., Lawlor D., Rimer J., Waugh F.,

McMurdo M., & Mead G. (2013). Exercise for depression.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 9(1). DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub6.

Danielsson, L., Noras, A., Waern, M, & Carlsson, J. (2013).

Exercise in the treatment of major depression: A systematic

review grading the quality of evidence. Physiotherapy Theory

Practice, 29(8), 573-85. doi: 10.3109/09593985.2013.774452.

Davidson, J. (2010). Major depressive disorder treatment guidelines

in America and Europe. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71(1).

Demyttenaere, K., Enzlin, P., Dewe,W., Boulanger, B., De BieJ,

A., Déja A., Troyer,W., et al. (2001). Compliance with

antidepressants in a primary care setting. Journal of Clinical

Psychiatry, 62(22), 30-33.

Dimeo, F., Bauer, M., Varahram, I., Proest, G., & Halter,

U. (2001). Benefits from aerobic exercise in patients with

major depression: a pilot study. BMJ Sports Medicine, 35,114-117.

Dunn, A., Trivedi, M., Kampert, J., Clark, C., & Chambliss,

H., (2005). Exercise treatment for depression efficacy and

dose response. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28(1),1-8.

Gelenberg, A. ( 2010). A review of the current guidelines

for depression treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry,

71(7). doi: 12.419/0878785.2013.7752.

Hassmen, P., Koivula, N., & Uutela, A. (2000). Physical

exercise and psychological well-being: a population study

in Finland. Preventive Medicine, 30, 17-25.

Helmich, I., Latini, A., Sigwalt, A., Carta, M., Machado,

S., Velasques, B., Ribeiro, P., & Budde, H. (2010). Neurobiological

alterations induced by exercise and their impact on depressive

disorders. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental

Health, 6(1), 115-125.

Hoffman, B., Babyak, M., Craighead, E., Sherwood, A., Doraiswamy,

M., Coons, M., & Blumenthal, J. (2011). Exercise and pharmacotherapy

in patients with major depression: one-year follow-up of the

smile study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 73(2), 127-133. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e31820433a5.

Kanning, M., & Schlicht, W. (2010). Be active and become

happy: an ecological momentary assessment of physical activity

and mood. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 32(2),

253-261.

Krogh, J., Videbech, P., Thomsen, C., Gluud, C., & Nordentoft,

M. (2012). Aerobic exercise versus stretching exercise in

patients with major depression. Public library of science

one, 7(10). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048316.

Kruisdijk, F., Hendriksen, I.,Tak, E., Beekman, A., &Rock,

M. (2012). Effect of running therapy on depression. BMC Public

Health; 12:50.

Lawlor, D., Hopker, S. (2001). The effectiveness of exercise

as an intervention in the management of depression. British

Medical Journal, 322, 1-8.

Nahas, R., & Sheikh, O. (2011). Complementary and alternative

medicine for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Canadian

Family Physician, 57(1).

Phillips, W., Kiernan, & M., King, A. (2003). Physical

activity as a nonpharmacological treatment for depression.

Complementary Health Practice Review journal, 8(2), 139-152.

Reed, J., & Buck, S. (2009). The effect of regular aerobic

exercise on positive- activated affect: A meta-analysis. Psychology

of Sport and Exercise, 10(6), 581-94.

Sayyadi, A., Nazer, M., Ansary, A., & Khleghi A. (2006).

The effect of the exercise training on depression in elderly

women. Annals of General Psychiatry, 5(1), 199-203. doi:10.1186/1744-859X-5-S1-S199.

Silveira, H., Moraes, H.,Oliveira, N.,Coutinho, E., Laks,

J., & Deslandes, A. (2013). Physical exercise and clinically

depressed patients: a systematic review. Neuropsychobiology

journal; 67(4), 61-68. DOI:10.1159/000345160.

Solomon, D., Keller, M., Leon, A., Mueller, T., & Lavori,

P. (2000). Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder.

American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(2), 229-233.

Stuart, G. (2001). Evidence based psychiatric nursing. Journal

of American Psychiatric Nurses association, 7, 103.

Townsend, M. (2011). Essential of Psychiatric Mental Health

Nursing: Concepts of care in evidence-based practice. 5th

Ed. F.A Davis. Philadelphia.p.371.

Underwood, M., Lamb, S., Eldridge, S… et al. (2013).

Exercise for depression in elderly residents of care homes:

a cluster-randomized controlled trial. The Lancet Journal,

382, 41-49.

World Health Organization. (2012). Global burden of disease

report. Disease prevalence and disability. Geneva: WHO; Retrieved

from

www.who.int/mediacentre/events/2012/wha65/journal/en/index4.html

|

|