| |

February

2014

- Volume 8, Issue 1

Assessing the

perception of nurses about privacy of patients

|

((2) ((2)

|

Manal AL-Bitawi

Ahmad AL- Omari

Correspondence:

Manal AL-Bitawi RN

PO box. 36033 Alhashmy Aljanoubi Amman Jordan 11120

Email: manalbetawy@yahoo.com |

Introduction

Privacy is a legal right of

patient/client, which flows from the fundamental rights to

life, liberty and property, drives from the right to enjoy

life and to be left alone (1+7+8). Respect for patients' privacy

and dignity are long established principles of nursing practice

(10). Invasion of a patient's privacy decreases the quality

of care that is provided for the patient and decreases the

trust of the patient in the medical team, which has a negative

effect on the health status of the patient (2+4).

The concept of patient privacy is

used in many disciplines and is recognized as one of the important

concepts in nursing (3+10). In the practice, there are many

forms for the patient privacy, including the physical, informational,

decisional and proprietary privacy (5). In fact, even though

most healthcare professionals know the limits of patient privacy

and its forms very well, they have trouble applying them to

their behaviors, particularly in hospital lifts where discussions

of patients' information may be overheard, or when the patient's

body parts need to be exposed (6+9). This gap between the

privacy perception and the privacy practice directs us toward

this study. The purpose of this study is to assess the current

practices and problems that are encountered with the perception

of patient privacy among registered nurses at King Hussein

Hospital.

Methodology

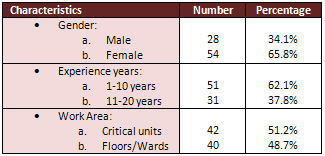

Descriptive design was used for this study. A convenience

sample of 100 registered nurses was selected from both genders

with different experiences, who are working in surgical and

medical floors, in addition to critical units at King Hussein

Hospital (Table 1).

Table 1: The characteristics of the sample

A questionnaire was developed by the researchers and consisted

of 20 statements that assessed mainly physical and informational

privacy. The four point Likert scale questionnaire was reviewed

by an expert panel consisting of nurse educator, nurse administrator

and senior nurse colleague to establish its content validity.

The stability reliability was checked by administering the

questionnaire to a group of 30 registered nurses selected

conveniently from both genders with different experiences.

Then after 2 weeks, the same instrument was administered to

the same group. The correlation coefficients were calculated,

and it was equal to (+0.80).

The Data collection was carried out

on 14th of January 2010. Response rate was 82% (n=82).

Results

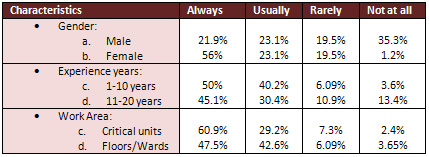

The patient privacy in our study was divided into two main

divisions: Physical privacy and Informational privacy. Physical

privacy includes preparing the environment that ensures patient

privacy before any procedure is provided to the patient, like

closing the room door or the drape, dismissing the visitors

and company. Physical privacy also includes obtaining patient

permission to expose any part of his/her body during any procedure.

In our study, 55.5% of the nurses were always protecting the

physical privacy, 34.9% usually, 7.4% rarely and 1.8% not

at all. (Table 2)

Table 2: The protecting of patients' physical Privacy

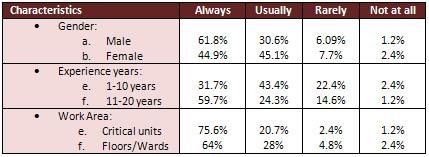

The other type of patient privacy

in our study was informational privacy, which includes protecting

all the information and records concerning patients, and not

sharing this information or records with anyone outside the

patient's medical team without the patient's permission. In

our study, just 18.5% of the study nurses were always protecting

the informational privacy, 21.9% usually, 26.5% rarely and

32.8% not at all (Table 3).

Table 3: The protecting of patients' informational Privacy

On the other hand, 53.6% of the study

nurses think that the most common invasions of the patients

privacy is caused by the visitors and patient's company. While

36.5% of the study nurses think that the most common invasions

of patient's privacy were caused by the health team members

themselves.

Discussion

Physical and informational privacy are the most well known

types of patient privacy among nurses (5). In the empirical

studies, the concept of privacy has mainly been studied in

hospital organizations using the physical dimension (5).

In our study, physical privacy was protected always &

usually by 90% of the participants, which reflects the high

standardized care that is provided by nurses. On the other

hand, the results show that female nurses protect physical

privacy more than male nurses, while the less experienced

nurses (1-10 years) protect the privacy more than the highly

experienced nurses (11-20 years). The less experienced nurses

are more restricted by the rules of the hospital. The work

area also has its effect on the physical privacy; in critical

units where there is a highly qualified team and more restriction

on the visitors, physical privacy is more protected (~80%)

than the floors.

The other type of privacy in our study is informational. Just

40.4% of the nurses were always and usually protect informational

privacy. This small percentage in comparison with the physical

privacy reflects the high need to train the nurses about how

to protect informational privacy. Gender also had its effect

on informational privacy; we find that the male nurses more

protect the informational privacy than females. In addition,

in the critical units informational privacy is also more protected

than on the floors. The previous studies found that informational

privacy was poorly protected in floors (10).

The causes for invasion of privacy in our study were the visitors

mainly, then by the medical team. In the previous studies,

the causes were mainly by the medical team not by the visitors

(4+6+10).

Conclusion

and Recommendations

An assurance of patient's privacy is necessary to secure effective,

high quality health care. Breaches of a patient's privacy

compromises ethical health care and undermines patients' confidence

in caregivers. Healthcare institutions must provide effective

training to minimize these breaches. We hope that the Royal

Medical Services will heed the call to improve discretion

for the patients who entrust us with their care.

References

1. Smeltzer, S., & Bare, B. (2003). Brunner and Suddarth's

textbook of medical-surgical nursing (10th edition). Philadelphia:

Lippincott. Chapter 3.pages (30-33).

2. Kozier, B., & Erb, G. (2004). Fundamentals of nursing

(7th edition). New Jersey: Pearson Education. Chapter 4. Pages

(58-61).

3. Bickley, L. S.,& Hoekelman, R. A (1999). Bates' guide

to physical examination and history taking (7th ed.). Philadelphia:

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

4. Day, L. J. , & Standard, D. (2006). Developing trust

and connection with patients and their families. Critical

Care Nurse, 19(3), 66-70.

5. Leino-Kilpi, H. Välimäki, T. Dassen, M. Gasull,

C. Lemonidou, A. Scott, M. Privacy: a review of the literature.

International Journal of Nursing Studies, Volume 38, Issue

6, December 2001, Pages 663-671.

6. Vigod, S. & Bell, C. Privacy of patients' information

in hospital lifts: observational study. BMJ 2003, 327; 1024-1025.

Available from: http://www.bmj.com/search/patientprivacy.html

7. American Nurses Association.(2009). Code of ethics for

nurses with interpretive statements. Washington, DC: American

Nurses Publishing.

8. Jordanian Nursing Council (2009). Code of ethics for nurse's

practice. Amman: Jordanian Nursing Council Publishing.

9. Haddad, A. (2001). Ethics in action. RN, 64(1), 29-30,32.

10. Rylance, G. Privacy, dignity, and confidentiality: interview

study with structured questionnaire. BMJ 2001, 318;301-303.

Available from: http://www.bmj.com/search/patientprivacy.html

|

|