| |

April

2014

- Volume 8, Issue 2

Effect of Combined

Interventions of Diet and Physical Activity on the Perceived

and Actual Risk of Coronary Heart Disease among Women in North

of Jordan

|

( (

|

Muneer Mohammad

Bustanji (1)

Sawsan Majali (2)

(1) Faculty of Nursing, AL-Hussein Bin Talal University,

Jordan

(2) Secretary General Higher Population Council, Jordan

Correspondence:

Dr. Muneer Mohammad Bustanji

Faculty of Nursing, AL-Hussein Bin Talal University,

Jordan

Email: mbustanji@hotmail.com

|

|

|

Abstract

Background and Aim: Women have received little

attention in cardiac research in Jordan. This study

aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of combined interventions

of diet and physical activity on the perceived and actual

risk for coronary heart disease among women in the north

of Jordan.

Methods: An experimental pretest/ posttest design

was used. The sample consisted of asymptomatic women

aged 40 years or older who lived in the north of Jordan.

The intervention involved recommendations concerning

healthy diet and physical activity to modify the actual

risk for coronary heart disease.

Results: The Kruskal-Wallis test; X2(2,

N = 134) = 46.62, p< 0.001, showed that women

who applied both diet and physical activity interventions

scored lower actual risk for heart disease than women

who only applied one type of intervention (either diet

or physical activity).

Conclusion: The results indicated the need for

constant national heart disease education programmes

for women emphasizing adopting healthy lifestyle behaviors.

Key words: Coronary heart disease, Diet, Physical

activity, Women, Risk.

|

Introduction

and Background

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) and stroke are rapidly growing

problems, and are the major causes of illness and deaths in

the Eastern Mediterranean Region, accounting for 31% of deaths

(Khatib, 2004).

Jordanian women were found to underestimate their risk for

coronary heart disease (CHD); and perceived breast cancer

as a greater risk to their health than CHD (Ammouri, et al.,

2010). Despite that, 28.9% of deaths among women in Jordan

were attributed to CHD and 23.5% were due to breast cancer

(JMOH, 2011). The majority of research on Jordanian women's

health has focused exclusively on reproductive health aspects

(AL-Qutob, 2001) and screening for breast cancer (Petro-Nustus

and Mikhail, 2002), and so far no study has been performed

which investigates the perceived and the actual risk of coronary

heart disease and or interventions that could reduce the risk

of CHD among women in Jordan.

This study aimed to assess the perceived risk and the actual

risk for coronary heart disease among women in the north of

Jordan. This study also aimed to evaluate the effectiveness

of combined interventions of diet and physical activity on

the perceived and actual risk for coronary heart disease among

women in north of Jordan.

Research Methods

Setting and Sample

A true experimental pretest/ posttest study was conducted

among a convenience sample of women who visited the out-patients

department at a university hospital and at a government hospital

(hospitals are located in the Irbid governorate). The inclusion

criteria of the sample were age is equal to or more than 40

years, willing to participate and not known to have CHD. The

sample size was estimated using power analysis which yielded

a sample size of 159 participants. In this study, the researcher

gathered data from 165 women to avoid the attrition risk.

Procedure

Phase One: Pretest Phase

After obtaining the approval to conduct the study from the

Committee on Human Research, the Jordanian Ministry of Health,

and the university hospital, the researcher visited the out-patient

department of each setting, where the women were invited to

participate in the study. Those who accepted to participate

in the study were asked to read and sign the informed consent

form. The form explained the purpose of the study, supplied

the woman with information about her rights as a participant,

and included directions for completing each of the forms.

In adherence with ethical standards, the informed consent

form also included information regarding confidentiality,

the intervention involved in the study, and a statement regarding

the participants' ability to withdraw from the study at any

time without penalty.

After signing the informed consent form, each woman completed

the survey forms; Demographic information sheet, and the Perception

of Risk of Heart Disease Scale (PRHDS). The PRHDS is a newly

developed and previously tested 20-item questionnaire composed

of three subscales: dread risk, risk and unknown risk (Ammouri

and Neuberger, 2008). These subscales are intended to place

individuals on a continuum from low perception of risk to

high perception of risk of CHD.

Dread risk, was defined at its high end as perceived lack

of control, dread, catastrophic potential, fatal consequences;

while unknown risk, was defined at its low end as perception

of hazards judged to be unobservable, unknown, new and delayed

in their manifestation of harm; and (in between) risk reflecting

a hazard that has few moderate known outcomes and consequences

(Ammouri and Neuberger, 2008).

Items were formatted using a four-point Likert scale ranging

from 1-4 (strongly disagree to strongly agree). To score the

instrument, item scores were summed for each subscale, as

well as across subscales for a total scale score; reverse

scoring of negative-response items is required (Ammouri and

Neuberger, 2008). Higher scores on the PRHDS subscales indicate

a higher perception of risk of CHD. Cronbach's alpha internal

consistency reliability coefficients of the original PRHDS

were .80, 0.72 and 0.68 for the dread risk subscale, the risk

subscale, and the unknown risk subscale respectively, with

a total scale reliability of .80 (Ammouri and Neuberger, 2008).

A test-retest correlation coefficient was also calculated

for the original version and yielded a total reliability of

0.72 with 0.76 for the dread risk subscale, 0.70 for the risk

subscale, and 0.61 for the unknown risk subscale (Ammouri

and Neuberger, 2008).

After completing the surveys forms, the researcher carried

out the physiologic measures (body height, body weight, blood

pressure, and blood glucose level). After weighing each woman

with the same scale, the researcher calculated the body mass

index of each woman using the results of height and weight

measurements.

Regarding measuring blood pressure, the researcher measured

the BP for each participant after ten minutes rest. Two independent

measurements of blood pressure were obtained with an interval

of at least ten minutes between them and the average BP was

calculated. For the purpose of this study, hypertension (HTN)

was defined as a person having a blood pressure equal to or

more than 140/90 mmHg or those individuals who are on antihypertensive

agents (AHA, 2010; National Institute of Health, 2002).

Regarding measuring blood glucose level, the researcher used

an Accu- Check machine, test strips, lancets, gloves, and

biohazard container. For the purpose of this study, a person

who has diabetes is defined as someone taking insulin or oral

hypoglycemic drugs, or with a fasting plasma glucose concentration

above 7.0 mmol/l (126 mg/dl).

After measuring the physiologic measures, the researcher used

the WHO/ISH risk prediction chart of the EMRO- B region without

cholesterol level to estimate the actual risk of CHD among

women (Figure 1). To estimate the actual risk using these

charts, the researcher collected data about the items included

in the charts; age, smoking status (all current smokers and

those who quit smoking less than one year before the assessment

were considered smokers for assessing cardiovascular risk),

blood pressure, and presence of diabetes mellitus. Then, the

researcher classified each participant into a category of

high risk (30% to <40% and >40%; red and maroon

color), medium risk (from 10% to <20% and from 20% to <30%;

yellow and orange), or low risk (<10%; green color) for

heart attack or stroke in the following ten years.

Click here for Charts

Phase Two: Intervention Phase

In this phase, the researcher randomly assigned the participants

into three groups (A, B, and C) and randomly also assigned

the interventions (diet and physical activity, diet part only,

or physical activity part only) to the groups. Eventually,

group A was assigned to the diet part of the intervention,

group B was assigned to both diet and physical activity interventions,

and group C was assigned to the physical activity part of

the intervention.

In this study, group B acted as the experimental group and

received both components of the intervention and group A and

C acted as the control groups and received only one component

of the intervention; either physical activity or diet component.

The researcher then provided a presentation for group A about

how to prevent CHD using the diet intervention only, a presentation

for group B about how to prevent CHD using both diet and physical

activity interventions, and a presentation for group C about

how to prevent CHD using physical activity intervention only.

Finally, the researcher emphasized to the women the importance

of following the guidelines for 12 weeks. Each four weeks

of this phase, the researcher contacted the participants in

order to make sure that they were committed to the guidelines

and to discuss any inquiry they had. Participants were contacted

via mobile phone.

Phase Three: Posttest Phase

After 12 weeks, the women individually returned to the out-patient

clinic to be reassessed for their physiologic measures and

to complete the PRHDS.

Educational Materials

The educational material was developed based on the "Pocket

guidelines for assessment and management of cardiovascular

risk with the WHO/ISH cardiovascular risk prediction charts

for WHO epidemiological sub-regions EMR- B, EMR- D" (WHO,

2007). The content of educational material was on how to prevent

occurrence of coronary heart disease through following specific

recommendations regarding diet and physical activity.

Regarding the recommendations about diet changes, women at

risk for CHD were strongly encouraged to reduce total fat

and saturated fat intake. In addition, they were strongly

encouraged to reduce daily salt intake by at least one-third

and, if possible, to <5 g per day. The women were encouraged

to eat at least 400 g a day, of a range of fruits and vegetables,

as well as whole grains. In addition, the women were strongly

encouraged to take at least 30 minutes of moderate physical

activity (e.g. brisk walking) a day, through leisure time,

daily tasks and work-related physical activity.

Results

Sample Characteristics

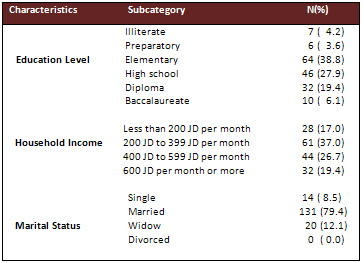

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the sample.

The mean age of the women in the sample was 52.6 (SD = 4.4)

ranging from 41 to 69 years. About 79.4% of the participants

were married, and the monthly household income of 17.0% of

the participants was less than 200 JD. More than half of the

women (53.4%) had a high school education or higher.

Table 1: Demographic Characteristics of the Sample (N =

165)

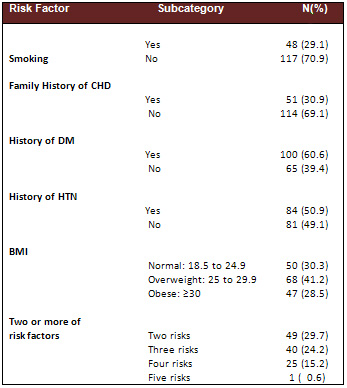

Risk Factors for CHD

The results indicated that 29.1% of participants were smokers,

30.9% had a family history of CHD, 60.6% were known to have

DM, 50.9% were known to have HTN, and 28.5% were obese (BMI

> 30). In addition, 69.7 % of the participants had multiple

risk factors for CHD (Table 2).

Table 2: Risk Factors for CHD (N= 165)

Level of Perceived Risk and the Actual Risk

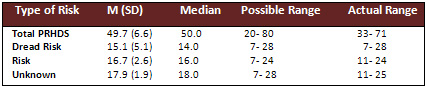

Table 3 provides data about the level of perceived risk among

the participants at the pretest phase of the study. The results

show that the mean score of total perceived risk was 49.7

out of 80.0, ranging from 33 to 71.

Table 3: Mean, Median, and Standard

Deviation of Perceived Risk at Pretest (N= 165)

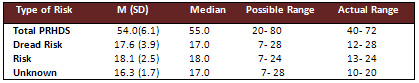

Table 4 shows data about the level of perceived risk among

the participants at the posttest phase. Note that, 31 women

from the original sample (N= 165) apologized for participating

in the posttest phase. The results show that the mean score

of total perceived risk was about 54.0 out of 80.0, ranging

from 40 to 72(N = 134). Whereas, the mean score of total perceived

risk for the same group (N = 134) was 48.6 out of 80.0 at

pretest phase.

Table 4: Mean, Median, and Standard Deviation of Perceived

Risk at Posttest (N= 134)

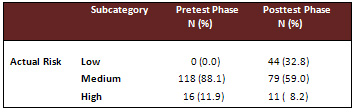

Regarding the level of the actual risk among participants

(Table 5), 32.8% of participants were at a low level of actual

risk for CHD according to the WHO/ ISH prediction charts.

Table 5: Percentages of Actual Risk (N= 134)

To evaluate the impact of intervention on the perception

level, a Paired sample t test was conducted to estimate the

difference in the mean score of the level of perceived risk

for CHD from the pretest and posttest phases of the study.

The results showed that there was a statistically significant

increase in the perception for CHD between the pretest phase

(M = 48.6, SD = 6.0) and the posttest phase (M = 54.0, SD

= 6.1), t (133) = -23.543, P<.0001. Since, the mean increase

was 5.4 with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 4.9 to

5.8, in addition, a Wilcoxon Signed Rank test was conducted

to evaluate the difference in the level of actual risk among

participants from the pretest and posttest phases of the study.

The analysis revealed a statistically significant reduction

in risk for CHD following participation in the program, Z

= - 6.486, P<0.001.

A Kruskal-Wallis test was conducted to evaluate differences

among the three types of interventions (diet only, diet and

physical activity, and physical activity only) on median change

in the level of actual risk for CHD. The test, which was corrected

for tied ranks, was significant X2(2,

N = 134) = 46.62, p< 0.001. The Mann-Whitney U test was

conducted to evaluate pairwise differences among the three

types of interventions, controlling for Type I error across

tests by using the Bonferroni approach. The results of these

tests indicated a significant difference in the level of actual

risk between the group who implemented both interventions

(diet and physical activity) and the group who only implemented

the diet intervention (U= 441.5, p< 0.001). Also, there

was a significant difference in the level of actual risk between

the group who implemented both interventions (diet and physical

activity) and the group who implemented the physical activity

intervention (U= 302.5, p< 0.001). Therefore, implementing

both interventions (diet and physical activity) elicited statistically

lower level of actual risk than implementing only one type

of intervention (p< 0.001). Note that, there was no statistically

significance difference in the level of actual risk median

between the group who implemented the diet intervention and

the group who implemented the physical activity intervention

(U= 922, p= 0.051).

Discussion

Perceived Risk of Heart disease

Several studies have found that a majority of women underestimated

their risk of heart disease (Lefler, 2004; Mosca, et al.,

2000; Mosca, et al., 2006, Ammouri, et al., 2010). This study

supports the work of others in pointing out the lack of awareness

among women about their susceptibility to this disease. In

the view of this fact, the mean of total score of the PRHDS

among women in this study was consistent with the mean of

total score of the PRHDS among participants in a study conducted

in Jordan by Ammouri, et al., (2010); of 43 out of 80 ranging

from 20 to 57. In addition, the mean score of unknown subscale

in this study was 17.9 out of 24 which corresponded with results

reported by Ammouri, et al. (2010); of 14.4 out of 24. These

results indicated that participants tend to downplay their

risk of heart disease.

Intervention

The results of the effectiveness of combined diet and

physical activity interventions that have been used in this

study are analogous to the results of other studies. Muto

and Yamauchi (2001) conducted a workplace health promotion

program targeting diet and exercise to reduce CVD risk among

152 employees in which the intervention group spent four days

at a resort for intensive lectures and training. The participants

were assessed at baseline and at three month intervals for

one year after the program. Those in the intervention group

showed significant improvements in body mass index, and systolic

blood pressure. Similarly, a 12 week employee wellness pilot

program involving university employees (N = 50) focused on

reducing risk factors for CHD through interventions aimed

at improving diet and implementing a consistent exercise regimen

(White and Jacques, 2007). The study's participants attended

monthly workshops and had pre- and post-intervention measurements,

which included weight, body composition, BP, TC, LDL-C, HDL-C,

TC/HDL-C ratio, TG, and blood glucose (White and Jacques,

2007). A significant difference was observed between pre-

and post-intervention measurements of weight (p = .01) (White

and Jacques, 2007). However, statistically significant improvement

was not seen in blood pressure. They also confirmed that only

25 of the original 50 participants remained (50%) at post-test,

which potentially skewed the results of an already miniscule

sample size (White and Jacques, 2007).

Limitations

One of the limitations of this study was the use of a

convenience sample which may not be truly representative of

women in Jordan. Although recruitment took place at several

local hospitals, generalizability is limited due to geographic

and nonrandom sample selection. Also, about 19% of participants

did not complete the post test phase.

Recommendations

Recommendations for Future Research:

• Conduct additional studies to include women with

less education, as well as women from different regions and

age categories.

• Conduct additional studies that include practical training

of the recommendations before starting the actual program.

• Conduct additional studies that include the WHO/ISH

risk predictions charts with cholesterol.

• Conduct qualitative research to understand why women

do not perceive themselves susceptible to heart disease and

why they do not practice behaviors that could reduce their

risk of developing heart disease and promote overall wellness.

Recommendations for Health Education Practice:

• There is a need for an increase in education regarding

personal risk factors for heart disease and devising strategies

to increase perceived susceptibility to the disease. It is

imperative that nurses help resolve common misperceptions

women have about heart disease and create increased awareness

of the disease. Current awareness campaigns have achieved

greater recognition of the impact of heart disease, but a

gap in awareness continues to exist. This gap might be narrowed

with more emphasis on social marketing through a media (i.e.,

television) available to the majority of the population.

• Exploration of the role of the physician recommending

heart disease screening is needed. In an effort to increase

screening behaviors of women, nurses can play a key role,

acting as a resource for both physicians and the community.

Nurses can help direct all women, whether they perceive themselves

as susceptible or not, to appropriate screening tests for

heart disease. Targeting younger women and those with lower

education levels also is necessary to reach a population that's

often under-represented in screenings.

• Health professionals, marketing experts, and non-profit

organizations, such as the Jordan Nursing Council, need to

collaborate to gain a better understanding of the priority

population's beliefs about heart disease and motivation to

participate in health-promoting behaviors to decrease risk

factors for heart disease. Marketing campaigns can be developed

to personalize the disease so women can relate to and understand

their vulnerability to the condition.

Conclusion

Cardiovascular risk factors should be assessed in women

starting much earlier than menopause and should then be treated

as aggressively in women as in men. Few women appreciate that

cardiovascular disease is their major health problem. So,

any woman can benefit from increased awareness of her risks,

and the younger women who adopt healthy lifestyle behaviors

now may avoid developing heart disease later in life.

References

1. Khatib O. Noncommunicable

diseases: Risk factors and regional strategies for prevention

and care. The Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 2004,

6: 778- 788.

2. Ammouri A, Neuberger G, Mrayyan

M, Hamaideh, S. Perception of risk of coronary heart disease

among Jordanians. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 2010, 20: 197-

203.

3. Mortality data in Jordan 2008.

Jordan Ministry of Health, 2011. (http://www.moh.gov.jo/MOH/En/publications.php/

accessed 20 June 2011).

4. Qutob R. Menopause- associated

problems: types and magnitude. A study in ain al-basha area,

Jordan. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2001, 33: 613- 620.

5. Petro-Nustus W, Mikhail B. Factors

associated with breast self examination among Jordanian women.

Journal of Public Health Nursing, 2001, 19: 263-271.

6. Ammouri A, Neuberger G. The perception

of risk of heart disease scale: Development and psychometric

analysis. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 2008, 16: 83-97.

7. Heart disease and stroke Statistics

2010 Update. American Heart Association, 2010. (http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/reprint/121/7/e46/

accessed 8 June 2011).

8. The National Cholesterol Education

Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP III) 2001. National

Institute of Health, 2002. (http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/cholesterol/atp3full.pdf/

accessed 2 August 2011).

9. Pocket guidelines for Assessment

and Management of Cardiovascular Risk with the WHO/ISH Cardiovascular

Risk Prediction Charts for WHO epidemiological sub-regions

EMR- B, EMR- D. World Health Organization, 2007. (http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/guidelines/PocketGL.ENGLISH.AFR-D-E.rev1.pdf/

accessed 2 August 2011).

10. Lefler L. Perceived risk of heart

attack: A function of gender? Nursing Forum, 2001, 39: 18-26.

11. Mosca L et al. Awareness, perceptions,

and knowledge of heart disease risk and prevention among women

in the United States. Archives of Family Medicine, 2000, 9:

506-515.

12. Mosca L et al. National study

of women's awareness, preventive action, and barriers to cardiovascular

health. Circulation-Journal of the American Heart Association,

2006, 113: 525-534.

13. Muto T, Yamauchi K. Evaluation

of a multi-component workplace health promotion program in

Japan on CVD risk factors. Journal of Preventive Medicine,

2001, 33: 571-577.

14. White K, Jacques P. Combined

diet and exercise intervention in the workplace: Effect on

CVD risk factors. American Association of Occupational Health

Journal, 2007, 55: 109-114.

|

|