| |

May

2016 - Volume 10, Issue 2

Methylnaltrexone or laxatives for the Management of Opioid-induced

Constipation among Palliative Patients on Opioid Therapy:

Evidence-based Review

|

( (

|

Mohammad

G. H. Tuffaha (1)

Nijmeh Al-Atiyyat (2)

(1)

Mohammad G. H. Tuffaha, R.N, BSc, MSN.

Hashemite University, School of Nursing, Zarqa, Jordan

Al-Bashir Hospital, Department of Hematology, Amman,

Jordan

(2) Dr. Nijmeh Al-Atiyyat, BSc, MSN, PHD.

Hashemite University, School of Nursing, Zarqa, Jordan

Correspondence:

Mohammad G.

H. Tuffaha, R.N, BSc, MSN.

Hashemite University, School of Nursing, Zarqa, Jordan

Al-Bashir Hospital, Department of Hematology, Amman,

Jordan

Email: mohammad_toffaha@yahoo.com

|

|

|

Abstract

Constipation is a common symptom in advanced cancer

patients. Studies have demonstrated that 40 to 80% of

patients on a palliative care service have constipation.

This proportion increases to > 90% when patients

are treated with opioids. Opioids are very effective

analgesics, frequently prescribed in cancer pain. Despite

proven analgesic efficacy the use of opioids is commonly

associated with frequently dose-limiting constipation

that seriously impacts on patients' quality of life.

Almost all patients on opioids report constipation as

the major side-effect. The aim of this article is to

determine the effectiveness of methylnaltrexone and

laxatives in the management of opioid-induced constipation

(OIC) among cancer patients in palliative care setting,

with focus on randomized clinical trials. A comprehensive

and extensive online database search of Science Direct

Database, PubMed, Springer Online Database, and HINARI/WHO

Database was conducted; also reference lists of related

studies were searched. Six studies fulfilling the inclusion

criteria from 1991 to 2009 were selected and formed

the basis for this paper. In three studies the laxatives

lactulose, senna, co danthramer, misrakasneham, and

magnesium hydroxide with liquid paraffin were evaluated,

and thirdly methylnaltrexone

. In studies comparing the different laxatives evidence

was inconclusive. Evidence on subcutaneous methylnaltrexone

was clearer; evidence on laxatives for management of

constipation remains limited due to insufficient RCTs.

Ultimately it can be suggested from the data presented

here that subcutaneous methylnaltrexone is effective

in inducing laxation in palliative care patients with

opioid-induced constipation and where conventional laxatives

have failed.

Key words: opioid-induced

constipation, methylnaltrexone, laxatives, cancer, management.

|

Background

Constipation is a common symptom in advanced cancer

patients. Studies have demonstrated that 40 to 80% of patients

on a palliative care service have constipation (Curtis, Krech,

Walsh, 1991; Sykes, 1998). This proportion increases to ?

90% when patients are treated with opioids (Sykes, 1998).

Fredericks, Hollis, & Carrie Stricker, (2010) define constipation

as less than three defecations per week (or change from usual

pattern), or the subjective symptom of difficult, infrequent,

or incomplete passage of stool that occurs in up to 90% of

patients with advanced cancer receiving opioids and can negatively

impact pain management and quality of life. Almost all patients

on opioids report constipation as the major side-effect. A

hospital survey showed that 87% of patients on strong opioids

required the use of laxatives. Among patients using morphine

80% reported constipation (Bouvy, Buurma, Egberts, 2002).

When opiates bind to the opiate receptors in the GI tract,

they interfere with peristalsis and the mucous secretion required

for bowel movements (Holzer, 2007; Mehendale, Yuan, 2006;

De, Cremonini, 2004; Holzer, 2004; Wood, Galligan, 2004; De,

Coupar, 1996). Use of exogenous opioids reduces peristalsis

(Mehendale et al., 2006), which, together with reduced secretion,

increased liquid reabsorption, and increased sphincter tone,

leads to the formation of dry, hard stools which are difficult

to pass (Pancha, Muller-Schwefe, Wurzelmann, 2007).

The impact of constipation on patients' quality of life is

important, especially for cancer patients (Choi & Billings,

2002) whose quality of life is already significantly impaired

by the illness itself. Constipation has been deemed by cancer

patients to be an even greater source of discomfort than the

pain they suffered (Fallon, 1999). According to World Health

Organization (WHO), opioids are very effective analgesics,

frequently prescribed in cancer pain (WHO, 1996). Despite

proven analgesic efficacy, the use of opioids is commonly

associated with frequently dose-limiting constipation that

seriously impacts on patients' quality of life (Reimer et

al., 2009). In addition to its negative impact on quality

of life, persistent constipation may lead to serious medical

sequelae, including bowel obstruction and fecal impaction,

may result in elevated use of prescription drugs and medical

services and may affect compliance with pain medications,

further compromising pain management strategies (Candrilli,

Davis, Iyer, 2009).

Therefore the purpose of this evidence-based review is to

answer the following PICOT question for an intervention/therapy,

where (P) stand for the population and primary problem, (I)

stand for intervention, (C) stand for comparison, (O) stand

for outcome, and (T) stand for time it takes to achieve an

outcome:

In patients with OIC, and they are cared for within the palliative

care unit (P), what is the effect of methylnaltrexone (I)

on the management of OIC (O) compared with laxatives (C) within

24 hours (T)?

Methods

Articles were retrieved for review via a combination of computer

and manual searches of selected opioid-induced constipation

and cancer-related publications. A comprehensive, and extensive

online database search of Science Direct Database, PubMed,

Springer Online Database, and HINARI/WHO Database was conducted

for opioid-induced constipation. Keywords used were "opioid-induced

constipation" "methylnaltrexone" "laxatives"

"cancer" "management" in multiple combination.

Also reference lists of related studies were searched.

The review utilized 6 articles, despite extensive search,

which met the inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were:

1. Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) 2. It investigated opioid-induced

constipation 3. Studies concerned adult participants receiving

palliative care. Based on this inclusion criteria a total

of 6 articles from 1991 to 2009 were selected and formed the

basis for this review.

Level of evidence of the included studies was rated based

on the work of Melnyk, Fineout-Overholt, (2005) and Stetler

et al., (1998). See table two in the appendix.

The six RCTs analyzed 498 participants; one study was of cross-over

design; the others were parallel design, of which three were

multi-center. The studies were undertaken in North American,

British, Spanish and Indian populations. All participants

were at an advanced stage of disease and were cared for within

a palliative care setting; most participants had a cancer

diagnosis. The average age of participants ranged from 61

to 72 years.

The drugs assessed were subcutaneous methylnaltrexone (Portenoy,

2008; Slatkin, 2009; Thomas, 2008) and the laxatives, all

taken orally, were senna (Agra, 1998; Ramesh, 1998; Sykes,

1991); lactulose (Agra, 1998; Sykes, 1991); danthron combined

with poloxamer (Sykes, 1991). One study also evaluated the

effect of misrakasneham; a drug used in traditional Indian

medicine as a purgative, containing castor oil, ghee, milk

and 21 kinds of herbs (Ramesh, 1998). In the studies on methylnaltrexone

nearly all participants (88% to 99%) were constipated at entry

despite taking one or more conventional laxatives.

Findings

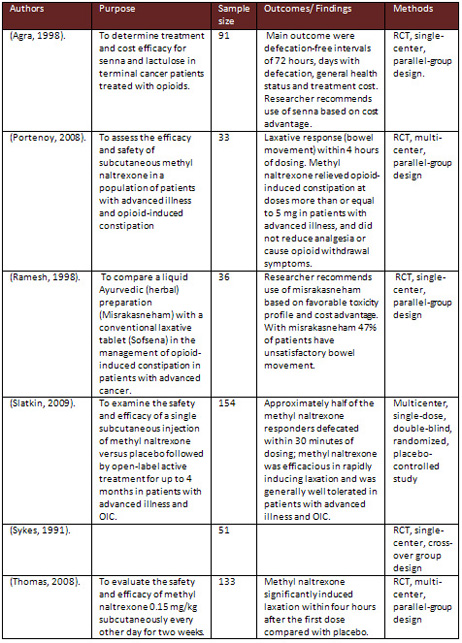

Descriptions of included studies in the review are displayed

through the table in the appendix.

Co-danthramer versus Senna plus Lactulose

One cross-over study of 51 participants evaluated the effectiveness

of co-danthramer versus senna plus lactulose (Sykes, 1991).

Both laxatives were in a liquid format.

Laxation responses: the researcher reports that

participants receiving 80 mg or more of strong opioid had

a significantly higher stool frequency when taking lactulose

plus senna than while receiving co-danthramer. While in a

lower dose of opioid, no statistical difference was reported.

Constipation-associated symptoms, pain intensity, opioid

withdrawal: not evaluated.

Acceptability and tolerability: diarrhea resulted

in suspension of laxative therapy for 24 hours for 15 patients

taking lactulose and for five patients taking codanthramer.

Researcher reported that six instances of diarrhea occurred

at opioid doses of at least 80 mg/day while taking lactulose

and senna; none were associated with co-danthramer. Two participants

reported perianal soreness and burning while taking codanthramer.

Participant preference was similar between the trial arms

(15 for lactulose and senna and 14 for co-danthramer), but

they also report that twice as many participants disliked

the flavor of co-danthramer compared to senna and lactulose.

Misrakasneham versus Senna

One small study of 36 participants evaluated the effectiveness

over two weeks of up to 10 ml of misrakasneham versus senna

24 mg to 72 mg (both in liquid format) (Ramesh, 1998).

Laxation responses: there was no statistical

difference between the misrakasneham and the senna groups

in satisfactory bowel movements. Six participants required

rescue laxatives, of which five were in the senna group.

Constipation-associated symptoms, pain intensity, opioid

withdrawal: not evaluated

.

Acceptability and tolerability: nausea, vomiting

and colicky pain were reported by two participants taking

misrakasneham. None of the participants withdrew due to inefficiency.

Participant preference was split between the groups.

Senna versus Lactulose

One study of 75 participants evaluated the effectiveness over

four weeks of lactulose 10 mg to 40 mg versus senna 12 mg

to 48 mg (both laxatives were in liquid format). Doses were

increased according to clinical response (Agra, 1998).

Laxation response: there was no statistical

difference between the senna and the lactulose groups in laxation

response. Thirty-seven percent of participants completing

the study required combined lactulose and senna to relieve

constipation.

Constipation-associated symptoms, pain intensity, opioid

withdrawal: there was no statistical difference in

the general state of health between the trial arms.

Acceptability and tolerability: three per trial

group, reported diarrhea, vomiting and cramps. There was no

significant difference in the number of participants who dropped

out between the trial arms.

Methylnaltrexone versus Placebo

Two studies evaluated subcutaneous methylnaltrexone versus

a placebo (Slatkin, 2009; Thomas, 2008). In one study a single

dose (0.15mg/kg or 0.30mg/kg) of methylnaltrexone was administered

(Slatkin, 2009); in the other study methylnaltrexone (0.15

mg/kg) was administered every other day for two weeks (Thomas,

2008).

Laxation response: participants who had a laxation

response at four hours ranged from 48% to 62% in the methylnaltrexone

trial groups and 13% to 15% in the placebo groups. At 24 hours

it was 52% to 68% in the active trial arms and 8% to 27% in

the placebo groups. A significant difference in laxation response

favoring the treatment group was also found in the multi dose

study at days three, five, seven, nine, eleven, and thirteen

(Thomas, 2008). In the single-dose study the researcher states

that the study demonstrated no dose-response relationship

(between 0.15 mg and 0.3 mg per kilogram doses) in laxation

and no correlation between laxation response and baseline

opioid dose (Slatkin, 2009). Dose response was not assessed

in the other study but at day eight, if participants had fewer

than three rescue-free laxations, the initial volume of the

study drug was doubled (to 0.30 mg of methylnaltrexone per

kilogram) (Thomas, 2008).

Constipation-associated symptoms, pain intensity, opioid

withdrawal: in the multi dose study they assessed

pain and symptoms of opioid withdrawal using the Modified

Himmelsbach Withdrawal Scale, at three time points; they found

no significant difference between the trial arms (Thomas,

2008). In the single-dose administration of methylnaltrexone

study there was no overall change from the baseline pain scores

or in having symptoms of opioid withdrawal (Slatkin, 2009).

Acceptability and tolerability: in the single-dose

study the researcher reports that during the double- blind

and subsequent open-label phase 19 participants experienced

severe adverse events that were possibly related to methylnaltrexone,

with some experiencing more than one event. These were: 15

incidents of abdominal pain, three of increased sweating,

two of increased pain and one each of burning at the injection

site, vomiting, diarrhea, asthenia, increased blood pressure,

dehydration, muscular cramps, loss of consciousness, tremor,

delirium, hallucination, dyspnea and flushing. In the same

study serious adverse events did not occur during the trial

phase but were reported in three participants during the subsequent

open-label phase. One participant had flushing and another

delirium possibly related to methylnaltrexone; a third had

severe diarrhea and subsequent dehydration and cardiovascular

collapse considered to be related to the drug (Slatkin, 2009).

In the other study they report that severe adverse events

occurred in 8% of participants in the methylnaltrexone group

and 13% in the placebo group (Thomas, 2008). The 11 serious

adverse events in those who received methylnaltrexone were:

aneurysm ruptured, respiratory arrest, dyspnea exacerbated,

suicidal ideation, aggression, malignant neoplasm progression,

concomitant disease progression, myocardial ischemia, coronary

artery disease aggravated and congestive heart failure aggravated.

The investigators considered all serious adverse events as

either not related or unlikely to be related to the trial

drug.

Dose Ranging Trial of Methylnaltrexone

One small study of 33 participants compared the effectiveness

of 1 mg (n = 10), 5 mg (n = 7), 12.5 mg (n =10) and 20 mg

(n =6) of subcutaneous methylnaltrexone (Portenoy, 2008).

Laxation response: the study reports that the

median time to laxation was 1.26 hours for patients dosed

at 5 mg or greater and in the 1mg group it was greater than

48 hours.

Constipation-associated symptoms, pain intensity, opioid

withdrawal: the researcher reports that there was

no evidence of methylnaltrexone-induced opioid withdrawal,

also there was not any difference in patient satisfaction

scores between the dose groups.

Acceptability and tolerability: all participants

experienced at least one treatment-emergent adverse event.

There was no significant difference between the lower dose

group compared to the other doses in the proportion of participants

who had a treatment related adverse event or discontinued

because of an adverse event. The types of adverse events were

similar between the dose groups. The most common adverse event

was abdominal pain. Two participants discontinued the trial

because of an adverse event. One was an 84-year old man who

withdrew due to syncope (12.5 mg dose). The event was transient

and resolved without sequelae; the investigators assessed

that it was related to the medication. A 20-year old man was

withdrawn after receiving three doses due to abdominal cramping,

assessed as probably related to the study medication.

Table 1: Description of included studies

Summary

This review sought to

determine the effectiveness of the administration of laxatives

and the opioid antagonist methylnaltrexone for the management

of constipation in palliative care patients. Six studies were

identified. Studies either compared the effectiveness of two

different laxatives, compared methylnaltrexone with a placebo

or different doses of methylnaltrexone. The effectiveness

of methylnaltrexone was not compared with a laxative and none

of the studies compared a laxative with a placebo; all comparisons

were made between different laxatives.

The review found that laxative use in the management of constipation

in this patient group is based on limited research evidence;

specifically, there have been no RCTs on any laxative that

have evaluated laxation response rate, patient tolerability

and acceptability.

There have been a few RCTs on the comparative advantages of

different laxatives. The limited evidence from these studies

suggests that the laxatives evaluated, including the commonly

used laxatives lactulose and senna, were of similar effectiveness

in this patient group. There is some evidence on the effectiveness

of methylnaltrexone, indicating that in comparison to placebo

and in patients where conventional laxative therapy is sub-optimal,

methylnaltrexone improves laxation.

References

Agra, Y., Sacristan, A., Gonzalez, M., Ferrari, M., Portugues,

A., Calvo, M.J. (1998). Efficacy of senna versus lactulose

in terminal cancer patients treated with opioids. Journal

of Pain and Symptom Management, 15, 1-7.

Bouvy, M.L., Buurma, H., Egberts, T.C.G. (2002). Laxative

prescribing in relation to opioid use and the influence of

pharmacy-based intervention. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy

and Therapeutics, 27, 107-110.

Candrilli, S.D., Davis, K.L., Iyer, S. (2009). Impact of Constipation

on Opioid Use Patterns, Health Care Resource Utilization,

and Costs in Cancer Patients on Opioid Therapy. Journal of

Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy, 23, (3), 231-241.

Chamberlain, B.H., Cross, K., Winston, J.L. (2009). Methylnaltrexone

treatment of opioid induced constipation in patients with

advanced illness. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management,

38, 683-90.

Choi, Y.S., Billings, J.A. (2002). Opioid antagonists: a review

of their role in palliative care, focusing on use in opioid-related

constipation. J Pain Symptom Manage, 24, 71-90.

Curtis, E.B., Krech, R., Walsh, T.D. (1991). Common symptoms

in patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Care, 7, 25-29.

De Luca, A., and Coupar, I.M. (1996). Insights into opioid

action in the intestinal tract. Pharmacology & therapeutics

69, 103-15.

De Schepper, H.U., Cremonini, F., Park, M.I., et al. (2004).

Opioids and the gut: pharmacology and current clinical experience.

Neurogastroenterol Motil 16, 383-94.

Fallon, M.T. (1999). Constipation in cancer patients: Prevalence,

pathogenesis, and cost-related issues. European Journal of

Pain, 3, 3-7.

Fredericks, A., Hollis, G., Stricker, C.T. (2010). Diagnosis

and management of opioid-induced bowel dysfunction in patients

with advanced cancer. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing,

14, (6), 701-704.

Holzer, P. (2007). Treatment of opioid-induced gut dysfunction.

Expert opinion on investigational drugs, 16, 181-94.

Holzer, P. (2004). Opioids and opioid receptors in the enteric

nervous system: from a problem in opioid analgesia to a possible

new prokinetic therapy in humans. Neuroscience letters 361,

192-5.

Melnyck, B.M. & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2005). Evidence-based

practice in healthcare. Philadelphia: Lippincott.

Mehendale, S.R, and Yuan, C.S (2006). Opioid-induced gastrointestinal

dysfunction. Dig Dis 24, 105-12.

Organization, WH (1996). Cancer pain relief. (Geneva: WHO).

Panchal, S.J., Muller-Schwefe, P., Wurzelmann, J.I. (2007).

Opioid-induced bowel dysfunction: prevalence, pathophysiology

and burden. Int J Clin Pract, 61, 1181-7.

Portenoy, R.K., Thomas, J., Moehl, Boatwright, M.L., Galasso,

F.L., Stambler, N., Von Gunten, C.F., et al. (2008). Subcutaneous

methylnaltrexone for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation

in patients with advanced illness: a double-blind, randomized,

parallel group, dose-ranging study. Journal of Pain and Symptom

Management, 35, 458-68.

Ramesh, P., Suresh Kumar, K., Rajagopal, M., Balachandran,

P., Warrier, P. (1998). Managing morphine-induced constipation:

a controlled comparison of the ayurvedic formulation and senna.

Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 16, (4), 240-4.

Reimer, K., Hopp, M., Zenz, M., et al. (2009). Meeting the

challenges of opioid-induced constipation in chronic pain

management-a novel approach. Pharmacology, 83, 10-17.

Slatkin, N., Thomas. J., Lipman, A.G., Wilson, G., Boatwright,

M.L., Wellman, C., et al. (2009). Methylnaltrexone for treatment

of opioid-induced constipation in advanced illness patients.

Journal of Supportive Oncology, 7, 39-46.

Stetler, C.B., Morsi, D., Rucki, S., Broughton, S., Corrigan,

B., Fitzgerald, J., et al. (1998). Utilization-focused integrative

reviews in a nursing service. Applied Nursing Research, 11,

195-206.

Sykes, N. (1991). A clinical comparison of laxatives in a

hospice. Palliative Medicine, 5, 307-14.

Sykes, N.P. (1998). Constipation and Diarrhea. In: Doyle,

D., Hanks, G., MacDonald, N., eds. Oxford textbook of palliative

medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 513-526.

Wood, J.D, and Galligan, J.J. (2004). Function of opioids

in the enteric nervous system. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 16,

17-28.

|

|